Michael Morris

Lauren Renee Sepulveda

With the Immigration and Customs Enforcement’s recent crackdown on illegal immigrants, many crime victims are scared. Here’s how one prosecutor office continues seeking justice when victims and witnesses are hesitant to come forward.

“No quiero problemas.” I don’t want problems.

As prosecutors along the Texas-Mexico border, we hear this statement with increasing frequency from our undocumented immigrant community. In our first years of working at the office, most prosecutors could assure our undocumented crime victims and witnesses that they could attend court settings and testify in the State’s case without fear of being taken into immigration custody. This is no longer true along the border and across the State of Texas.

On February 9, 2017, shortly after President Donald Trump signed an executive order expanding the categories of undocumented immigrants eligible for deportation, Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) agents showed up outside an El Paso County courtroom and detained Irvin González, a transgender woman and undocumented immigrant, who was in court seeking a protective order against an abusive ex-boyfriend. After the hearing, she was taken into custody, and the story exploded internationally. Several media outlets reported that González’s abusive ex-boyfriend was the person who called immigration authorities on her. El Paso County Attorney Jo Anne Bernal was quoted in media stories that she couldn’t remember a time in her 23 years at the courthouse that immigration officials ever targeted a person seeking a protective order in court. Many prosecutors in our office worried that the newly enforced immigration guidelines might mean that undocumented crime victims and witnesses would be reluctant to report crime and cooperate with investigations. We were also concerned that defendants had new incentive to call immigration authorities to report their victims.

Predictably, amid this backdrop of growing deportation fears among the undocumented community, the reporting of crime—especially sexual assaults and domestic violence—in the Hispanic community has fallen. This past March, Houston Police Chief Art Acevedo reported that the number of Hispanics reporting rape in his city is down 42.8 percent, and the reporting of other violent crimes has dropped 13 percent from the first quarter of 2016. These numbers fell despite an overall increase in crime reporting in the Houston area.

We’ve also noticed that undocumented witnesses and victims have become less likely to cooperate with ongoing criminal investigations; jurisdictions to the north are reporting similar issues. In this new climate of increased fear among undocumented victims and witnesses, what can prosecutors do to assure the administration of justice and protect witnesses and victims?

When the undocumented victim or witness is not in ICE custody

When our office’s Victims Assistance Unit first contacts undocumented victims and material witnesses who are not in immigration custody, we take a proactive approach in educating them about their immigration situation. Our victim advocates give them information and documentation showing they are a victim or witness in an ongoing criminal investigation. We ask that the person tell someone trustworthy where that documentation is, should he or she be taken into immigration custody, so that those documents can be turned over to immigration authorities. Our Victims Assistance Unit notifies victims that if they are taken into ICE custody, they should not sign any voluntary removal paperwork because they are a necessary witness to an ongoing criminal case and that they should immediately notify the agency and their deportation officer of the situation. At that first meeting, our victim advocates begin screening for possible immigration relief in the form of U-visas, T-visas, or the Violence Against Women Act (VAWA) (more about all of these later).

The Travis County District Attorney’s Office in Austin has started a more formal program in which undocumented victims and witnesses are given letters from the prosecutor’s office to carry with them. These letters explain they are victims or key witnesses in the prosecution of an ongoing case and are to be presented if they are approached by a law enforcement officer or questioned as to their immigration status. While Travis County’s program is new, we should note that these letters—as well as any of the documents provided by our own office’s Victims Assistance Unit—do not give the holder legal immigration status or have any legal authority whatsoever. ICE has issued a statement about the Travis County program, saying: “ICE continually strives to work with our law enforcement partners to increase public safety. All immigration cases are reviewed on a case by case basis.” ICE officials have not guaranteed they would honor these letters or documents.

U-visas. If an undocumented victim or witness qualifies to apply for a nonimmigrant U-visa under the Victims of Trafficking and Violence Act, our victim advocates begin the paperwork as soon as possible. The U-visa is a form of immigration relief that allows victims and witnesses of certain crimes who have been certified as helpful to the prosecution by a law enforcement agency, to apply for legal status in the United States. (Read more about U-visas at www.tdcaa.com/journal/understanding-u-visas.)

As deportation fears have risen, so has the number of U-visa applications. In the spring of 2016, our office was receiving about 12 applications a week—that number has risen to 30 a week as of late. U-visas, however, are often not the magic answer that undocumented victims, witnesses, and prosecutors may be looking for. Even after an immigrant is certified and files the application, it takes two to three years before he receives permission to work legally in the United States and about four to five years before he receives legal immigration status. These waiting periods may be further increased given the volume of applications in recent months. Additionally, the number of available U-visas is capped by federal law at 10,000 per fiscal year. As of January 2016, there was a backlog of 64,000 applications—a number likely to swell even further.

T-visas. Our Victims Assistance Unit also screens victims for T-visa eligibility under the Victims of Trafficking and Violence Act, which is meant for victims of severe human trafficking crimes. Unlike U-visas, T-visas do not have legislated caps for distribution, and their time table for issuance of work visas and legal status is much faster.

VAWA petitioning. If the victim does not qualify for a T-visa, we also screen for self-petitioning under VAWA. Unlike the U-visa program, a petitioner under VAWA must be a victim of a crime committed by a U.S. citizen or legal resident. VAWA’s timetables are much shorter than the U-visa or T-visa programs—most applicants, if accepted, receive their letter of approval within three months and can begin to apply for public benefits at that time. Within six to eight months, they are issued a work permit and legal documentation, such as a Social Security number. There is no legislated cap to the number of applicants who can qualify under VAWA.

Prosecutors should note that any application by a victim or witness for any of these adjustments of legal status should be disclosed to defense counsel pursuant to Tex. Code Crim. Proc. Art. 39.14.

When the undocumented victim or witness is in ICE custody

Once someone has been detained for removal purposes, prosecutors have a couple of options to secure their appearance so we can continue the prosecution of our case.

Some offices may ask ICE for a Deferred Action (DA) or an Administrative Stay of Removal (ASR) for witnesses or victims who have been taken into immigration custody. A law enforcement agency can request a DA on an undocumented person whether he is in or out of ICE custody. Receiving a DA for an undocumented immigrant means the government has decided it is not in its interest to arrest, charge, prosecute, or remove an individual at that time for a specific, articulable reason. The authority of ICE to grant a DA is discretionary, and officials review several factors in each case. Unlike a U-visa, T-visa, or an adjustment of status under VAWA, a DA does not confer any immigration status upon the holder and does not cure any defect in his immigration status, and ICE can commence removal proceedings against the holder at any time. If a DA is granted for an undocumented immigrant currently in ICE custody, then the grantee can be transferred to state custody. A DA is granted for a specific period of time determined by ICE.

If the undocumented witness or victim is subject to a final order of removal but has yet to be removed from the United States, the State can request an Administrative Stay of Removal (ASR). An ASR is also a discretionary tool used by ICE to release those needed to testify in the prosecution of a case involving a violation of federal or state law. An undocumented person who is granted an ASR may be released from immigration custody upon the filing of an approved bond, an agreement to appear, and other prescribed conditions. Much like a DA, an ASR does not cure any immigration status defect, and after the case is disposed, the grantee will again be subject to removal.

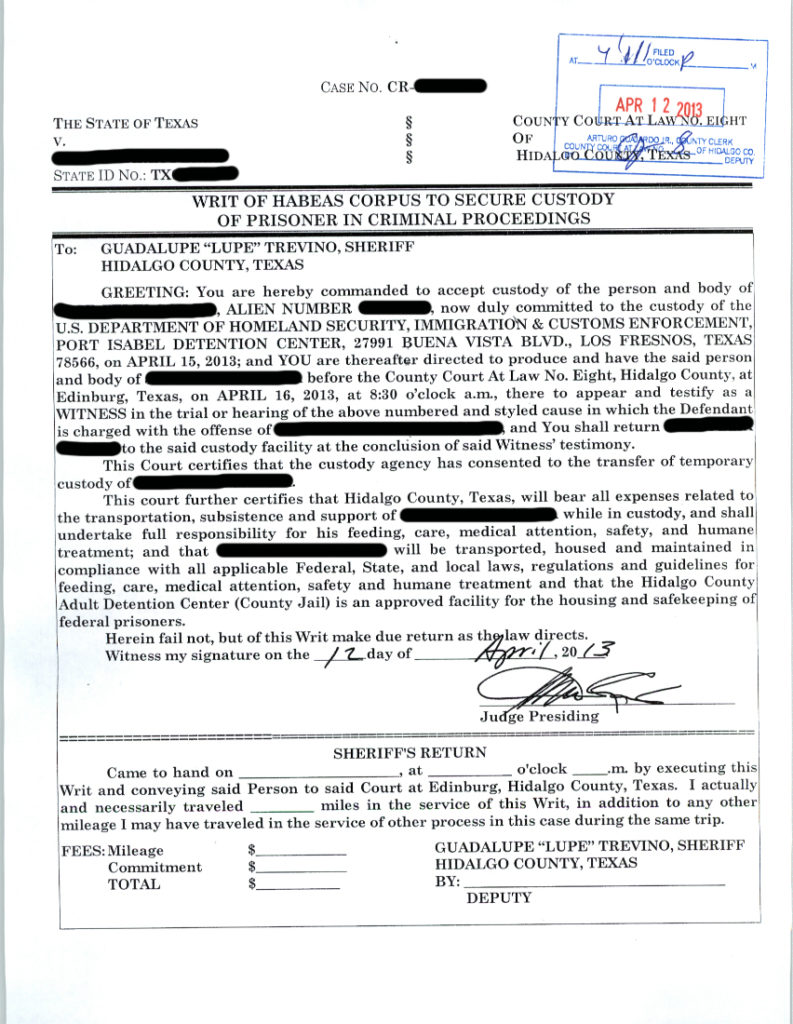

In past cases where witnesses and victims were already in removal proceedings and an ASR or a DA was not deemed appropriate, ICE has allowed us to file a Writ of Habeas Corpus to Secure Custody of Prisoner in Criminal Proceedings to remove them from immigration custody to testify at trial. (An example from a previous case is below.) However, it should be noted that ICE indicated that if the writ is for a future trial date, the undocumented person is still subject to removal and could be deported in that time frame. It is up to ICE officials, in other words, whether they want to honor the writ.

Perhaps the greatest tool a prosecutor has once a witness or victim has been taken into immigration custody is the consulate from his country of origin. Our Victims Assistance Unit maintains a good relationship with local consulates and lets those officials know once we’ve found that a victim or witness has been taken into immigration custody. If a witness has suddenly stopped communicating with our office, the consulates can help determine if that person is in an immigration detention center. Once the consulate is made aware that one of their citizens has been detained, that person will be provided with legal help through the consulate, commonly known as a proteccion familiar. If a victim or witness is incarcerated at an immigration detention center, our Victims Assistance Unit may also attempt to connect the person in custody with immigration services through Texas RioGrande Legal Aid (TRLA) or another local agency.

When a victim or witness has already been deported

Even if the victim or witness has been deported, the State of Texas still has some options that can allow us to proceed with prosecution.

Once an undocumented crime victim or witness is removed from the United States, it may be hard to find her in her country of origin. However, prosecutors can request the help of that person’s consulate in locating her once she’s been removed. If the victim or witness has been removed from the United States but is an admissible alien (that is, she does not fall into one of the classes of aliens ineligible to receive visas or ineligible for admission), she can still apply for status through a U-visa from her country of origin with the help of her consulate.

Law enforcement agencies may request a Significant Public Benefit Parole (SPBP) to bring a removed person into the United States. SPBP is a temporary measure that allows an otherwise inadmissible alien into the United States temporarily, but it does not constitute formal admission into the country. However, much like a DA or an ASR from ICE custody, the victim or witness who is granted SPBP must return to her country of origin once the case is disposed.

What if a defendant has successfully had a victim or witness deported to keep her from testifying against him in court?

Texas law may allow the State to proceed in certain cases. Texas Code of Criminal Procedure Art. 38.49, the Forfeiture by Wrongdoing statute, states that a party to a criminal case who wrongfully procures the unavailability of a witness or prospective witness may not benefit from the wrongdoing by depriving the trier of fact of relevant evidence and testimony. The party then forfeits the right to object to the admissibility of evidence or statements based on the witness’s unavailability. Texas’ statute goes beyond the common-law doctrine of forfeiture by wrongdoing and allows the State to use testimonial hearsay of an absent witness or victim, getting that testimony around any Crawford or hearsay objections. To qualify for forfeiture by wrongdoing, the defendant’s action that procured the witness’ unavailability doesn’t need the sole intent to keep the victim from testifying, and the defendant’s action does not have to be a criminal offense or threat. (Read an article on the forfeiture by wrongdoing at www.tdcaa.com/journal/forfeiture-wrongdoing-%C2%ADdoctrine-nine-years-after-crawford.)

Although we could find no caselaw directly on point in Texas or any other state, we did find some indication that the doctrine of forfeiture by wrongdoing would apply where a defendant procured the unavailability of a victim by having her deported. In State of New Mexico v. Mario Hector Alvarez-Lopez, the defendant was spotted at the scene of a burglary but evaded capture. The victim of the burglary caught the defendant’s accomplice, who implicated the defendant in the crime. The defendant absconded before trial and, in the years that passed, the accomplice was convicted and deported from the United States. When the defendant was finally captured and tried, an officer read the accomplice’s statement into evidence. When the defendant ap-pealed the conviction, the State of New Mexico contended that the defendant forfeited the right to confront his accomplice because his absconding had procured the accomplice’s deportation.

The Supreme Court of New Mexico found, based on the common-law doctrine of forfeiture by wrongdoing, that although the deportation may, in an indirect sense, have been a consequence of the defendant absconding, the causal relationship between the two was not sufficient to satisfy the common-law forfeiture by wrongdoing doctrine. The opinion suggests that to use the forfeiture by wrongdoing doctrine, the State had to show that the act of absconding had intended to procure the accomplice’s unavailability. In the absence of facts that showed the defendant’s motive in absconding was to silence his accomplice, the State failed to meet its burden of proving that the defendant intended or was motivated to produce the accomplice’s unavailability. Alvarez-Lopez seems to suggest that if the State could prove a defendant was motivated to procure a witness’s deportation and committed an act that did so, the defendant would have waived his right to confrontation under the forfeiture by wrongdoing doctrine. Because Texas’ forfeiture by wrongdoing statue is more expansive than the common-law doctrine explored in Alvarez-Lopez, it stands to reason that prosecutors could use the doctrine to introduce testimonial hearsay of a victim or witness deported by a defendant’s actions.

Conclusion

As we navigate the growing fear of deportation in immigrant communities, it is important that prosecutor offices across the state—in border regions and elsewhere—continue to communicate and share techniques for prosecuting crimes that involve undocumented immigrants. In 2011, ICE notified its agents that they should exercise discretion in cases involving victims and witnesses of crime to minimize the effect immigration enforcement may have on the willingness of victims, witnesses, and plaintiffs to call police and prosecute crimes. Absent special circumstances or aggravating factors, it was against ICE’s policy to initiate removal proceedings against an individual known to be the immediate victim or witness of a crime.

Due to the recent executive order expanding the categories of undocumented immigrants subject to deportation, it is unclear whether ICE’s policies remain the same as they were in 2011. In this time of uncertainty, by using pre-existing tools to secure the availability of our witnesses and by blazing new paths using forfeiture by wrongdoing, we must continue to encourage undocumented immigrants to keep reporting crime and participating in prosecutions. The looming threat of deportation complicates—but does not obstruct—that goal. We must continue to strive to seek justice for our community, both documented and undocumented. (A special thanks to Victims Unit Program Director Rosie Martinez for her help in researching this article.)

Endnotes

1 Katie Mettler, “’This is really unprecedented’: ICE detains woman seeking domestic abuse protection at Texas courthouse,” The Washington Post (February 16, 2017), www.washingtonpost.com/ news/morning-mix/wp/2017/02/16/this-is-really-unprecedented-ice-detains-woman-seeking-domestic-abuse-protection-at-texas-courthouse.

2 Jonathan Blitzer, “The Woman Arrested by ICE in a Courthouse Speaks Out,” The New Yorker (February 23, 2017), www.newyorker.com/ news/news-desk/the-woman-arrested-by-ice-in-a-courthouse-speaks-out.

3 James Queally, “Latinos are reporting fewer sexual assaults amid a climate of fear in immigrant communities, LAPD says,” Los Angeles Times (March 21, 2017), www.latimes.com/local/ lanow/la-me-ln-immigrant-crime-reporting-drops-20170321-story.html.

4 Brooke A. Lewis, “HPD chief announces decrease in Hispanics reporting rape and violent crimes compared to last year,” Houston Chronicle (April 6, 2017), www.chron.com/news/houston-texas/houston/article/HPD-chief-announces-decrease-in-Hispanics-11053829.php.

5 Id.

6 Jennifer Medina, “Too scared to report sexual abuse. The fear: deportation,” The New York Times (April 30, 2017), www.nytimes.com/2017/ 04/30/us/immigrants-deportation-sexual-abuse.html.

7 Ryan Autullo, “Immigration advocates hopeful ICE honors Travis DA’s letter program,” Austin American-Statesman (May 30, 2017), www.mystatesman.com/news/local-govt—politics/immigration-advocates-hopeful-ice-honors-travis-letter-program/wlxMoIkrpEnKmOTH7w48qK/

8 Id.

9 U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Service, https://www.uscis.gov/humanitarian/victims-human-trafficking-other-crimes/victims-criminal-activity-u-nonimmigrant-status/victims-criminal-activity-u-nonimmigrant-status (last visited May 25, 2017).

10 U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, https://www.ice.gov/doclib/about/offices/osltc/pdf/tool-kit-for-prosecutors.pdf (last visited May 31, 2017).

11 Hansi Lo Wang, “Immigration Relief Possible In Return For Crime Victims’ Cooperation,” NPR (January 20, 2016), www.npr.org/2016/01/ 20/463619424/immigration-relief-possible-in-return-for-crime-victims-cooperation.

12 U.S. Citizenship & Immigration Services, https://www.uscis.gov/humanitarian/victims-human-trafficking-other-crimes/victims-human-trafficking-t-nonimmigrant-status (last visited May 25, 2017).

13 U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, www.ice.gov/doclib/about/offices/osltc/pdf/tool-kit-for-prosecutors.pdf (last visited May 31, 2017).

14 Id. at 5.

15 Id. at 6.

16 Id. at 7.

17 Id.

18 Id. at 9.

19 www.uscis.gov/ilink/docView/SLB/HTML/ SLB/0-0-0-1/0-0-0-29/0-0-0-2006.html.

20 Id. at 24.

21 Id.

22 Tex. Code Crim. Proc. Art.38.49(a).

23 See Gonzalez v. State, 195 S.W.3d 114, 117-19 (Tex. Crim. App. 2006).

24 See Tex. Code. Crim. Proc. Art. 38.49(d)(1); Shepherd v. State, 489 S.W.3d 559, 575 (Tex. App.—Texarkana 2016, pet. ref’d); United States v. Jackson, 706 F.3rd 264, 269 (4th Cir. 2013).

25 State of New Mexico v. Mario Hector Alvarez-Lopez, 98 P.3d 699, 702 (N.M. 2004).

26 Id. at 703.

27 Id. at 704.

28 Id. at 705.

29 Ryan Autullo, Immigration advocates hopeful ICE honors Travis DA’s letter program, Austin American-Statesman (May 30, 2017), www.mystatesman.com/news/local-govt—politics/immigration-advocates-hopeful-ice-honors-travis-letter-program/wlxMoIkrpEnKmOTH7w48qK/.

30 Id.