By Andrea Westerfeld

Assistant County & District Attorney in Ellis County

It’s a common experience in courtrooms around the state and around the country: The defendant is found guilty, the judge pronounces the punishment, and the defendant is led out of the courtroom to begin serving his sentence. The victims and their families heave a sigh of relief, knowing that the defendant will be facing justice and their ordeal in the criminal justice system is over.

But elsewhere in the courthouse, the appellate attorney is just getting started. To the public—and often to the other members of the DA’s Office as well!—the appellate process is long, mysterious, and confusing. Victims who hear that their case is being appealed may be gripped with fear that the case will be overturned and uncertainty about what is going to happen next. They look to the victim assistance coordinator (VAC) to find answers, but often the VAC is just as confused about the process as they are.

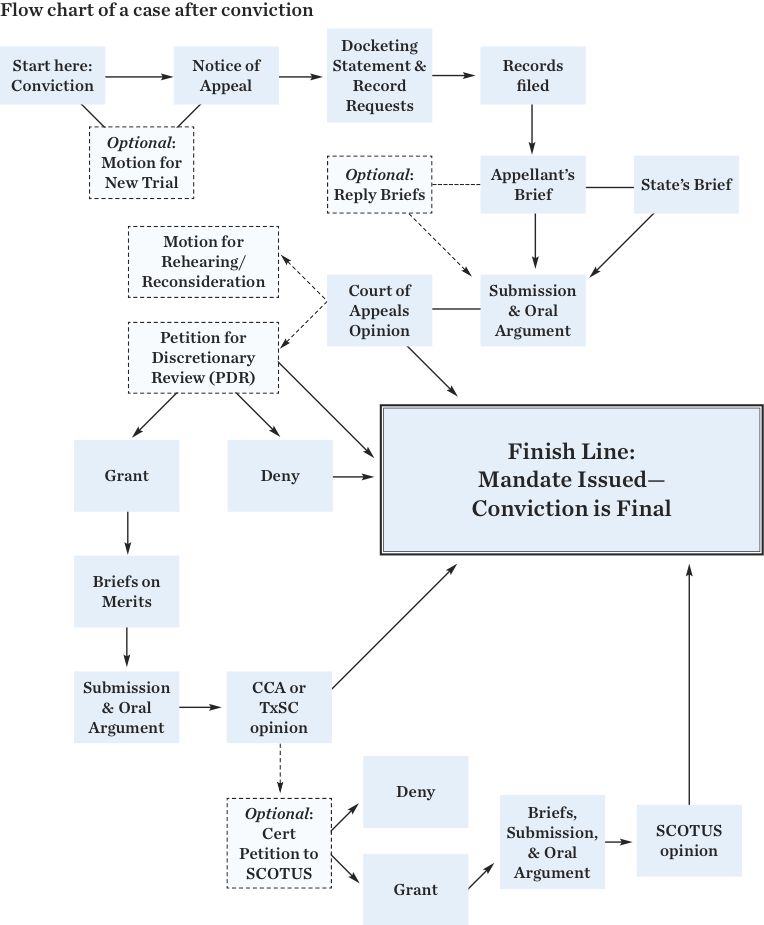

In this article, I break down the appellate process so VACs can understand what is going on, and I’ve included a timeline of a case after the verdict comes in. Please note that this does not cover cases where the defendant received a death sentence—those have distinct rules and timelines. But all other criminal cases share the same timelines.

Notice of appeal

The first step to appealing is the notice of appeal. This is simply the defendant letting the courts know that he intends to appeal his case. It is filed with the court where he was convicted, referred to as the trial court.[1] Notice must be filed within 30 days from the date the defendant is sentenced in open court.[2] He can get up to an extra 15 days if he files a motion for extension.[3] If he does not file this motion in time, then he will not be able to appeal his case. If he timely files his notice, the defendant will now be known as the appellant.

At this point, the appellant can request an appellate bond from the trial court.[4] A person who was sentenced to more than 10 years in prison or was convicted of certain offenses is not able to get an appeal bond.[5] An appeal bond acts just like a pretrial bond, requiring the appellant to pay money and follow certain conditions while his appeal is pending.

Optional: Motion for New Trial

The defendant has another option within 30 days of his conviction. He can file a motion for new trial, which is a sort of mini-appeal directly to the trial court instead of the appellate courts.[6] If the defendant has new evidence of something, such as his attorney making significant errors or jury misconduct, he may have a hearing to have the issue resolved. But often, a motion for new trial is filed just to extend the appellate timeline if the defendant is not sure he wants to appeal. If a motion for new trial is filed, then the deadline to file a notice of appeal extends to 90 days from the judgment.[7]

Procedural matters

At this point, there are a number of different procedural matters that the appellant must do for the appeal to go forward. He must file a docketing statement with the appellate court, which just gives the court basic information such as what type of case it is (criminal, civil, or family), the attorneys’ contact information, the name of the judge and court reporter, etc.[8] This is not something for which the court will dismiss the case if it is not filed in time. It is just administrative.[9] The court will simply request that the appellant file it as soon as possible.

The appellant also has to file requests with the local clerk—district clerk for felonies, county clerk for misdemeanors—and the court reporter who handled the trial to prepare the clerk’s and reporter’s records.[10] The clerk’s record is a collection of all the official papers in the case, such as the indictment, motions filed by either side along the way, the jury charge and verdict forms, and any post-conviction motions such as a motion for new trial and notice of appeal.[11] The reporter’s record is a transcript of the trial itself. Sometimes an appellant will request a transcript of only the actual trial, while sometimes he may ask for all the hearings that were held before the trial started too. Nothing can be appealed unless there is a record to show what happened. The record must be filed within 60 days from the date sentence was imposed, or 120 days from the filing of a motion for new trial.[12] The clerk or reporter can request an extension if they need more time, such as if it was a very long trial with a lot to transcribe.[13] Again, this is not something that will get a case dismissed if deadlines are not met.[14] The courts will send reminders and may eventually hold a reporter in contempt, requiring her to finish in a certain time or even be jailed until she finishes in extreme cases. But if the appellant never pays for the records even after being reminded by the court, the appeal may be dismissed for want of prosecution.[15]

After the reporter’s record is filed, the appellate court (also called an intermediate court or court of appeals) becomes the main court on the case. The trial court loses jurisdiction, meaning it cannot act unless the appellate court specifically asks it to (usually to hold a hearing because something was not done earlier) or the appeal is final.[16] There are 14 intermediate appellate courts in Texas. They are referred to by the city they’re based in, although they cover a much broader area than just that city. For example, my cases from Waxahachie are all filed in the 10th Court of Appeals in Waco. Each court makes its own rulings and is not bound by what the other intermediate courts do. Sometimes cases are transferred between the different courts to even out the number of cases per court.

Appellant’s and State’s Briefs (30 days each)

After the records are filed, the clock starts ticking for the appellant’s brief. This is a written document, usually 20–30 pages but sometimes longer, where the appellant explains everything he thinks went wrong in the trial. That may be evidence he thinks should not have been admitted, problems with closing arguments, witnesses who should or should not have been allowed to testify, problems with the instructions given to the jury, or any number of other issues. The appellant has 30 days from when the later of the clerk’s or reporter’s record was filed to file his brief.[17] However, he can request extensions.[18] A first extension of 30 days is very common in appellate cases. Longer extensions can be granted, but it depends on the court where the case was filed.

After the appellant’s brief is filed, the State’s timeline to file its own brief starts. This gives us the opportunity to explain why the appellant is wrong and there were no mistakes in his trial that require overturning the conviction. We have 30 days from when the appellant’s brief is filed to file our brief.[19] Again, extensions may be granted depending on the court.

Optional: Reply briefs

Most cases are decided on just one brief from each side. But if the appellant decides the State’s brief needs a response, he can file a reply brief. He has 20 days from the filing of the State’s brief to file a reply.[20] In some cases the State may reply in turn, but any further reply briefs would be at the discretion of the court and would not extend any other deadlines.

Submission and oral argument

Submission is when the court of appeals officially receives the case and starts to consider it. The submission date can be set any time after the briefs are filed and the time has expired to file a reply brief, but how long it takes depends on the individual court of appeals. The court may decide that in addition to the briefs, it wants to hear oral argument from the attorneys on the case.[21] This is a chance for the attorneys to go before the court and explain their position in more detail, and an opportunity for the justices to ask questions about issues that concern them. If there is oral argument on a case, it is submitted as soon as the argument is finished. Some appellate courts grant oral argument more frequently, while others hardly ever grant it. Oral argument is not required to decide a case, so it is not done in every instance.

Court of appeals opinion

This is the part of an appeal everyone pays the most attention to, where the court of appeals decides what to do with the case. There are three basic outcomes—affirm, reverse and remand, or reverse and render.[22] An affirmance is what we all want to see on an appeal. It means the appellate court decided either that there was not error or that it was not so serious that the appellant deserves a new trial, so it upholds the conviction.

Reversing is what we do not like, because it means the court has decided that there was a serious error. Reversing and remanding means that the case is sent back to the trial court and the case can be tried again, this time without the error. The case could have a whole new jury trial, there could be a plea bargain, or the case can be dismissed, usually if crucial evidence was thrown out.

A reverse and render is much rarer, and it’s for the most significant of errors where the court entirely throws out the conviction and issues an acquittal instead. This usually happens only when the appellate court decides the State did not prove a part of its case.

Regardless of how the appeal is decided, the court of appeals issues a written opinion where the judges explain why they decided each point of error that the appellant raised.[23] These can be a page or two long, or they can run hundreds of pages, depending on the complexity of the appeal.

Mandate

Technically all the other steps listed below are considered optional. They are chances for the losing side to ask someone to reconsider or review the case again in hopes of getting a different decision. But if no one files any of those motions, then the appellate court issues the mandate.[24] A mandate is a document that basically says the appeal is finished. Once there is a mandate, the appeal bond is revoked and the appellant begins serving his sentence (if his conviction was affirmed) or he is released from confinement or bond (if his conviction was reversed). Nothing happens in the trial court during an appeal unless the appellate court asks it specifically to do something or the mandate has issued.[25] The mandate is the State’s finish line. But as you can see from the flow chart below, this is only the first of many different ways a case can get to the mandate!

Motions for rehearing and reconsideration en banc

After the appellate court decides the case, whichever side lost may ask the court to look at the case again. Now, not all intermediate appellate courts are the same size. They all have at least three justices, but the largest in Dallas has 13 justices. When there are more than three justices on a court, a panel of three justices is assigned to hear each case.[26] In a motion for rehearing, the losing side asks the same panel that decided the case to reconsider.[27] This motion may point out an error that was made or sometimes a new case that just came out and should have been considered. If the court has more than three justices, the losing side can file a motion for reconsideration en banc, which means asking the entire court to look at the case. The losing party has 15 days after the opinion was issued to file a motion for rehearing or reconsideration en banc.[28] If that party chooses to file a motion for rehearing first, it has another 15 days after that is denied to still file a motion for reconsideration en banc.[29] Either of these may receive an extension within 15 days, making the deadlines effectively 30 days.[30]

Petition for Discretionary Review (PDR)

Unlike when the same court is asked to reconsider its decision, a petition for discretionary review, or PDR, is essentially a chance to ask the high court to grade the intermediate court’s work. In Texas, all criminal appeals go to the Court of Criminal Appeals (CCA).[31] This court has nine judges and sits in Austin. It is the final word in Texas on criminal cases.

A big difference between intermediate appellate courts and the CCA is that the CCA has the discretion to take a case or not.[32] Intermediate courts must take an appeal as long as all deadlines are met and it is filed in the right place. But to convince the CCA to step in, the losing party on appeal must file a PDR. The party can do this regardless of whether it filed a motion for rehearing or reconsideration en banc.[33] The PDR lays out the reasons why this case is significant to the law of the entire state, not just of concern to the people involved in it. The losing party has 30 days from the intermediate court’s opinion to file a PDR, with 15 days to request an extension if necessary.[34] The other side has 15 days after that to file a response.[35]

The CCA takes many fewer cases than are filed, so the odds are low that any given case will be accepted. If the CCA does not decide to hear the case, it sends the case back to the intermediate court within 15 days, and that court will issue the mandate.[36]

Proceedings in the CCA

If the CCA does decide to hear a case, then we start over at the briefing stage, meaning both sides write another brief to explain why the intermediate court’s opinion was right or wrong.[37] This is referred to as a “brief on the merits,” to distinguish it from the PDR that merely says why the case is important. After the briefs are filed, the case is set for submission and possibly oral argument.[38] Oral argument is granted more frequently in the CCA than in most of the intermediate courts, so it is often a part of the decisions.

Unlike the intermediate courts, all nine CCA judges decide each case rather than sitting on smaller panels. That means there can be no later en banc reconsideration because the entire court has already heard the case. When they have reached a decision, they will issue a written opinion just like the intermediate courts to explain the reason for their decision.[39] They can either uphold the court of appeals or reverse it. Sometimes the CCA decides to send a case back down to the court of appeals, usually because it found an error and the lower court needs to reconsider its decision or other parts of the appeal because of that error. If that happens, there may be another intermediate court decision and potentially even another PDR.

Whenever the case is finally decided by the CCA, the lower court of appeals will issue the mandate once the timeline for all motions for rehearing are passed.[40] This means the CCA’s opinion is now final.

Proceedings in the Supreme Court of the United States

One final path the losing party on appeal can take is asking the Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) to hear the case. Like the CCA, SCOTUS is a purely discretionary court, and it takes an even smaller percentage of cases than the CCA does. That means most appellate prosecutors will go their entire careers without having a case taken up by SCOTUS.

The path to the Supreme Court is filing a petition for writ of certiorari, usually just called a cert petition. It must be filed within 90 days of the CCA’s opinion or denial of PDR.[41] If SCOTUS decides to take the case, called granting cert, the briefing, submission, and oral argument schedule starts all over again, with 45 days from cert being granted to file the initial brief, and another 30 days for the response.[42] Then we wait for the nine SCOTUS justices to decide the case and issue a written opinion. Filing a cert petition does not stop the timeline for a mandate to issue, so a case is not affected by a pending cert unless the cert is granted. SCOTUS issues its own mandate 32 days after the entry of the judgment, and at that point the case is completely final.[43]

Conclusion

As you can see, the appellate process is a long one with many steps along the way. Unfortunately, while some things operate by a strict timeline, other things have no definite time by which they must be completed. That makes it very hard to gauge exactly how long an appeal will take. A simple one can be done in a few months, while others may take a year or longer.

The important thing is to be patient and keep in communication with whoever handles the appeals in your office. They can tell you more about your particular intermediate court of appeals and keep you apprised on what stage the appeal is at. Also remember that you can check the progress of an appeal yourself at the appellate court’s website, www.txcourts.gov. i

Endnotes

[1] Texas Rule of Appellate Procedure 25.2(c)(1).

[2] Tex. R. App. P. 26.2(a)(1).

[3] Tex. R. App. P. 26.3.

[4] Tex. Code Crim. Proc. Art. 44.04.

[5] Tex. Code Crim. Proc. Art. 44.04(b). Offenses that are never eligible for an appeal bond include murder, kidnapping, most sexual offenses, and offenses involving a deadly weapon.

[6] Tex. R. App. P. 21.

[7] Tex. R. App. P. 26.2(a)(2).

[8] Tex. R. App. P. 32.2.

[9] Tex. R. App. P. 32.4.

[10] Tex. R. App. P. 34.5(b), 34.6(b).

[11] Tex. R. App. P. 34.5.

[12] Tex. R. App. P. 35.2.

[13] Tex. R. App. P. 35.3(c).

[14] Tex. R. App. P. 34.5(b)(4), 34.6(b)(3), 35.3(c).

[15] Tex. R. App. P. 37.3(b) & (c).

[16] Tex. R. App. P. 25.2(g).

[17] Tex. R. App. P. 38.6(a).

[18] Tex. R. App. P. 38.6(d).

[19] Tex. R. App. P. 38.6(b).

[20] Tex. R. App. P. 38.6(c).

[21] Tex. R. App. P. 39.1.

[22] Tex. R. App. P. 43.2.

[23] Tex. R. App. P. 47.1.

[24] Tex. R. App. P. 18.1(a). Mandate issues at least 10 days after the time has expired to file a PDR or motion for rehearing.

[25] Tex. R. App. P. 25.2(g).

[26] Tex. R. App. P. 41.1(a).

[27] Tex. R. App. P. 49.1.

[28] Tex. R. App. P. 49.1, 49.7.

[29] Tex. R. App. P. 49.7.

[30] Tex. R. App. P. 49.8.

[31] Civil and family appeals go to the Texas Supreme Court. These two courts are co-equal high courts, meaning each one is the final word in its area. Prosecutors only go to the Texas Supreme Court for a few cases, including termination of parental rights, juvenile cases, expunctions, and nondisclosures. The process works the same way, except the Supreme Court calls a PDR simply a petition for review.

[32] Tex. R. App. P. 66.2.

[33] Tex. R. App. P. 49.9.

[34] Tex. R. App. P. 68.2.

[35] Tex. R. App. P. 68.9.

[36] Tex. R. App. P. 69.4(a).

[37] Tex. R. App. P. 70.

[38] Tex. R. App. P. 75.1.

[39] Tex. R. App. P. 77.1.

[40] Motions for rehearing must be filed within 15 days, with an extension allowed within 15 days of that deadline. Tex. R. App. P. 79.1, 79.6.

[41] Supreme Court Rule 13.1.

[42] Supreme Court Rule 25.

[43] Supreme Court Rule 45.2.