By Emily Dixon & Lisa A. Callaghan,

Assistant Criminal District Attorneys, &

Danny Nutt

CDA Investigator, all in Tarrant County

There are some cases so horrific that you remember where you were when you first reviewed them. You remember everything about them. They are impossible to forget, even when you want to.

Such is the case of Craig Alan Vandewege, who on a crisp December day in 2016 executed his wife and 3-month-old son by cutting their throats. He then reported for work as a set-up for his alibi. He was prepared to get away with murder.

But as is often the case in criminal investigations, there was much more to this crime than just the events of December 15, 2016. Mr. Vandewege’s scheming and planning started much earlier. His financial planning and motivation to commit this crime started years prior and escalated in the year before he killed his wife and son. After a lengthy investigation by Detectives Matt Barron and John Galloway of the Fort Worth Police Department, plus five years of work by the prosecutors and investigators at the Tarrant County Criminal District Attorney’s Office, a jury gave the final word and decided the fate of Craig Vandewege. As appeals are final and mandate has issued, the story can finally be told.

Background of the crime

Craig Vandewege and Shanna Riddle met on Christian Mingle. They both lived in Colorado at the time. To Craig’s parents, it seemed that they were very much in love. Her parents thought the same, although there was always something about Craig that bothered them.

Shanna was a nurse and Craig worked for Costco as an optician. A promotion within Costco brought them to Fort Worth.

On the evening of December 15, 2016, Vanderwege called 911 after arriving home from work to report finding his wife’s and child’s bodies in the bedroom. He told the 911 dispatcher that they were deceased and that the “house was messed up,” suggesting that an intruder, perhaps a burglar, had been inside. Two things caught the dispatcher’s attention: that the caller’s reporting of events seemed to focus more on making his report than on asking for help, and that his emotional demeanor was not consistent with someone who had just found his family dead. In fact, she described him as calm, and he did not ask for help, which was very unusual in her experience of receiving calls from people in similar situations. A witness with Medstar, who testified concerning its portion of the 911 call, described Vanderwege’s demeanor on the phone as “nonchalant,” and also said it was unusual because of a “lack of wanting to help.”

Police arrived about four minutes after the 911 call and discovered Vanderwege in front of the house waiting for them. He was calm in his demeanor when speaking to the first officer and had no tears in his eyes, nor did he appear to be in shock.

Going upstairs in the darkened house, officers encountered a scene of incredible horror. Shanna was in her bed, in a position suggesting she was asleep at the time of her death, with her throat cut. She was wearing night clothes and a mouth guard, which also suggested she’d been sleeping when she was killed. The baby, Diederik, was in his bassinet next to her, also with his throat cut. All blood was confined to the bed and bassinet; there was no indication of a fight taking place in the bedroom. There was also no obvious weapon in the room. However, it did appear that there was blood under the lip of the sink and in the sink itself in the adjacent bathroom, as though someone might have tried to clean up there.

Vanderwege, meanwhile, was informed he was not under arrest, and he was given the opportunity to speak with homicide detectives. He agreed to go downtown to the Fort Worth Police Department for an interview. He showed no significant emotion during this interview, and in fact actually slept a little while waiting for detectives to come speak to him. In his statement, he attempted to pawn the situation off as a burglary. He said he left around 10:30 the morning of the murders. Shanna and the baby were sleeping, he said. He started texting his wife around 2 o’clock that afternoon, and he texted her for an hour, but she did not respond. When he got home and found them, he took no life-saving measures, as they were obviously deceased.

At the crime scene

While detectives worked on Vanderwege in the interview room, crime scene officers began the painstaking process of going over the house in detail. The first officer to enter noted that cabinets in the kitchen were opened, but nothing appeared to have been rummaged through or ransacked. As more officers arrived, more things were noticed. There were pry marks on the back door, but no windows or glass in the door was broken. It did not look as though it had been kicked open either. There were expensive items, including televisions and firearms, in obvious places that were not taken. Shanna’s purse, containing credit cards, money, and medication, was untouched in the kitchen. There were dogs in the house at the time of the victims’ deaths, and a shotgun under the bed, but it did not appear that Shanna responded to the dogs barking, nor did she make any attempt to pull the shotgun out from under the bed. There were two safes on the floor, one with a key in it and whose contents were dumped on the floor. The other safe had to be opened with a code.

Crime scene officers made a thorough search of the house and of Vanderwege’s vehicle in the driveway, which he told detectives he had driven to and from work that day. Of interest in the front console was a white rubber examination-type glove that had multiple reddish- brown stains on it. This glove would prove very significant once DNA testing was done.

What Vanderwege did next

Vanderwege left the police department after the first interview and went to work “because he had nowhere else to go,” he said. He told a supervisor at Costco that “someone had broken into the house” and his wife and son were killed. The supervisor asked another employee to drive him to a hotel, as his home was still being processed by a crime scene team. His demeanor, once again, was described as “stone-faced.”

The other Costco employee described his conversation with Vanderwege about what happened. Vanderwege said he arrived home from work that evening and found the front door unlocked, which he thought was odd. He noticed dog urine on the floor and disarray in the kitchen, and eventually he went up upstairs to the bedroom. He said the bedroom door was closed, which was also odd to him. He looked in the room and discovered the bodies of his wife and child, but he did not approach them. He told this coworker that nothing was missing from the house, and he insinuated he was in the house while the crime scene unit was doing its job, and that they were examining the pry marks on the back door. This, of course, was false. Vanderwege also said that whoever committed the crime must have made Shanna open the safes before they killed her. But this was inconsistent with the crime scene because there was no sign of a struggle—there would have surely been one if she had been awake when killed, but it appeared she was asleep when she died. This coworker also noted the Vanderwege didn’t call either victim by name while he was speaking of them.

Vanderwege left Fort Worth around December 20 and drove to Colorado. While there, he posted on Facebook, which came to the attention of the police department. It was something along the lines of a farewell note:

“So, after taking a little drive and stopping at the local Chevy dealership, I told the salesman my life story. He agreed to let me borrow a newer Corvette. He has all my guns and has Shanna Riddle Vandewege’s Elantra. I want to meet you all in Las Vegas at Trump Tower and ask Trump for a pardon in case lying [expletive] face investigator convicts me. I feel the deck is stacked against me. I am going to get 2K out of the bank and do some hookers and cocaine while one gives me a [vulgar] job. Maybe he will let me grab someone by the [vulgar]. I love you all and God bless and God speed and [vulgar] deep. Yee, yee.”

He stopped at a convenience store in Glenwood Springs, Colorado, and made some odd statements to the clerk about people being taken into custody for a murder, and the clerk subsequently called police. Glenwood Springs officers initiated a traffic stop and detained Vanderwege, and he continued making odd statements. He told them his wife and son had been murdered and pointed out he had multiple firearms in his car. He also told them he was being blamed for the murders, but that his dad told him the “good news” that someone else was arrested, and he was going to Las Vegas.

Initially, this stop became tense because Vanderwege refused to get out of the car, but he was ultimately arrested and taken to jail. Soon after, Detective Barron in Fort Worth obtained an arrest warrant for capital murder after being notified of his suspect’s arrest in Colorado.

Capital murder charges were filed in Tarrant County. Although this case was subject to the death penalty, a decision was made by then-District Attorney Sharen Wilson not to pursue it. Therefore, if Vanderwege were convicted, the only punishment available was life without parole.

Investigating

Prosecutors Lisa Callaghan and Robert Huseman, with CDA Investigator Danny Nutt, made a fact-finding trip to Colorado in January 2017. It was clear there were a lot of witnesses there who needed to be interviewed in detail and sorted through, plus new witnesses to discover. After a week we had talked to Costco employees, family friends, and others, giving us a richer understanding of the situation.

Many of the defendant’s former coworkers recalled him saying things about both Shanna and the baby that were concerning and derogatory. He criticized everything about Shanna: her looks, weight, money management skills, intelligence, and more. He complained about their sex life and how she dressed, that it was not “sexy” enough. He also said that after having the baby, Shanna had gained weight and “looked like a bodybuilder,” and it disgusted him. He said he made her cry every day because he was “an asshole.” Vanderwege’s colleagues at Costco, both in Colorado and in Fort Worth, said he made these comments to them almost daily. There was also information from multiple sources (cell phones and online posts) that Vanderwege was interested in sex outside the marriage.

In Tarrant County at that time, it was common for a case of this magnitude to take two or three years to work its way up to the top of the trial docket and actually go to trial. During those years, much work was done. It became clear, for example, that a financial motive might explain the defendant’s crimes, and that possibility had to be researched and records ordered. Forensic testing had to be done. All of this was normal, but then something unexpected happened—the pandemic hit. For almost two years the courts were shut down, so this case pended for almost five years before it got to trial. In that time, Robert Huseman left the DA’s office, and Emily Dixon signed on to be second chair. Finally, after so many years of waiting, the day came—October 20, 2021, the day we picked the jury in this case.

The trial

At trial, about 30 witnesses testified. The jury was very business-like and remarkably attentive. This was particularly beneficial to the State, as one of the jurors became ill with Covid-19 and the trial had to be continued for about a week mid-trial. It was gut-wrenching, but ultimately it was only a brief delay. Another juror was declared disabled, and she was replaced with an alternate, and the trial started again. This time, however, jurors were not in the jury box together; they were spread out in the spectator gallery, as far apart from each other as possible. The proceedings were streamed to an adjoining courtroom so that family and spectators could watch, as was proper under existing law.

One of the witnesses who testified, Amanda Rickerd, did serology testing on the glove from the console of the defendant’s car. He had driven it to work, after leaving his wife and child in the morning, and then returned that evening to find them murdered. Therefore, if he was telling the truth (that he had not been in the house when they were killed), you would not expect to find blood evidence in his car. According to Ms. Rickerd, the glove had human blood on it. She took swabs and submitted them for DNA testing. Lo and behold, the defendant could not be excluded from a stain on the wrist of that glove; the chance that an unrelated person chosen at random from the general population would be included as a contributor to this major DNA profile was approximately one in every 320 sextillion individuals. However, the most important result was that another stain was consistent with baby Diederik’s DNA. The chance that an unrelated person chosen at random from the general population would be included as a contributor to this DNA profile was approximately one in every 1.3 quintillion individuals. There was no innocent explanation for a glove of this type to be found in the cab of his car with his DNA and his child’s blood on it. It was, in fact, a smoking gun.

In addition, the blood in the sink where the killer appeared to have cleaned up was a combination of the defendant’s, Shanna’s, and the baby’s blood; the blood under the lip of the sink was Shanna’s. The other DNA in the house was notable for one additional thing: Of all the items tested for DNA (from the kitchen drawers, the bathroom sink, and other locations), no sign of foreign DNA was present in that house. The only profiles came from the defendant, Shanna, and the baby, meaning there were no foreign profiles present (where lab techs were able to obtain a profile). This absence, in its own way, was also a smoking gun. It suggests, of course, that no one broke in or touched anything—the only surviving person in that house was Craig Vandewege. He was the only person who could have committed these crimes.

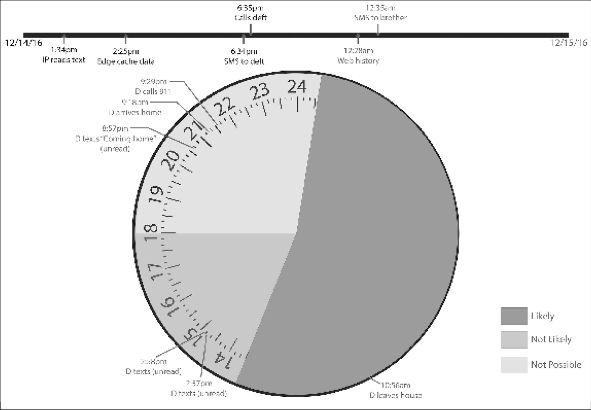

The medical examiner also testified for the State. In addition to describing the injuries to the throats of both victims, she discussed their likely times of death. For this purpose, our office’s Forensic Litigation Support Specialist Rhona Wedderein created what we liked to call a “time wheel.” (It is reprinted below.) It showed relevant times, including the last known communications from Shanna; when the defendant left for work; when the 911 call was made; and other events to show that during the times she and the baby were likely alive, Vanderwege was the only person around. Shanna last communicated using her cell phone at 12:35 a.m. The defendant called 911 at 9:29 p.m. that night. Dr. Tasha Greenberg, the medical examiner, testified that based on rigor and fixed lividity, it was most likely that Shanna had been killed between 12:35 a.m. and approximately 1:30 p.m. that afternoon. There was no one in contact with either victim from 12:35 a.m. to 10:56 a.m. (when the defendant left for work) other than him. There was no one else present who could have killed Shanna and Diederik.

A blood spatter expert from the Montgomery County Sheriff’s Office also testified that the blood evidence from the photos was consistent with Shanna being in her bed in the position she was found in immediately prior to her death. There was a blood marking on her chin and face indicating that someone whose hand was already bloodied had touched her there. From all evidence it was consistent with her being asleep when the bloodletting began. It is not clear, however, which of the two victims died first.

The State also called Jeanette Hanna, a forensic financial analyst who is employed with the DA’s office, to testify. It became clear to our team during the preparation of the case that the defendant had taken out an unusual amount of insurance on Shanna and the baby. Fortunately, Jeanette was able to do some digging, and in combination with subpoenaed information from Costco and other insurance providers, a financial motive quickly became clear. Although Shanna already had some life insurance on her a month after she and Craig Vandewege were married, he took out additional insurance on her in the amount of $220,736, for a total of $265,000, before they moved to Texas. Once they got here in 2016, the defendant took out even more insurance, including accidental death and dismemberment insurance. There was a total of $661,505 in life insurance on Shanna prior to her death.

On Diederik, the defendant took out $56,500 in life insurance, much of which was accidental death and dismemberment insurance—very unusual for an infant. The defendant obtained the insurance on the baby two days after he was born. The total amount of insurance on both victims was $718,005, and the beneficiary of all the policies was Craig Vandewege.

In addition, once the family home in Aspen was sold (when they moved to Texas), that money was put into a living trust accessible only by the defendant. Four days after the murders, he disbursed $25,000 to his mother; a little over a month after the murders, he gave an additional $199,000 to his father. Vanderwege benefitted to the tune of $973,842.21 from the deaths of Shanna and the baby.

The verdict

The jury went out to deliberate at 12:40 p.m. on November 4, 2021, and they reached their verdict at 3:55 p.m., just a little over three hours later. From the State’s perspective, it was the longest three hours in history.

At one point after we closed our case, we went to an adjoining room where Shanna’s family and friends had observed final argument. Many had come from out of state to watch, and they were all crying. Not just crying, but gut-wrenching sobs, letting out years of pain. It was very difficult to see, but somehow it pointed out the ability of trials to exorcise pain and help people heal. Somewhere in all that pain was a small seed of hope.

When the verdict came back, the jury foreman announced with great conviction that they had reached a verdict, and Judge Robert Brotherton read it: “We, the jury, find the defendant, Craig Alan Vandewege, guilty of the offense of capital murder, as charged in the indictment.”

After five years, justice was finally done.

After the appellate process concluded, mandate was issued on June 6, 2024. Vanderwege was taken to the Institutional Division of the Texas Department of Criminal Justice, where he remains at the Clemens Unit on a sentence of life without parole to this day. While Shanna and Diederik were not there to see that verdict, their loved ones were.

Conclusion

Shanna and Diederik Vandewege deserved to live their lives to the fullest. Shanna deserved to pursue her career as a nurse, to become a grandmother, and to have a dignified old age. Diederik deserved to go to school, grow up, become a man, and get married one day. They both deserved love and loyalty. They were denied all these things by the one man who should have done everything he could to see that their lives were full and happy. Instead, he betrayed them—and for what? For a worthless “freedom” to follow his vices: sex and greed.

The only silver lining in this tragedy is that the person who authored it will pay for it—in the Texas Department of Criminal Justice—for the rest of his life.