By Robyn Beckham,

Assistant Criminal District Attorney in Kaufman County, &

Leslie Odom,

Assistant County & District Attorney in Ellis County

Introduction from Leslie Odom

As a CPS (Child Protective Services) prosecutor in Ellis County, I’m sure I am not alone in thinking, “I wish The Texas Prosecutor included more perspectives and knowledge from CPS attorneys.” After nearly 17 years as a prosecutor, most of that time spent representing the Texas Department of Family and Protective Services (TDFPS), I’ve often wished that those of us representing CPS could have more of a voice in journals and trainings. Like many attorneys in similar roles, I have served as the sole CPS prosecutor in my county for almost the entirety of my practice of child protection law, and it is a role that can feel quite isolating, as if you work on an island all by yourself.

Imagine my excitement when TDCAA reached out and invited me to share my voice and perspective in this space! This is the first in a series of six articles exploring key aspects of prosecution from a CPS attorney’s point of view. My hope is to foster stronger understanding and collaboration between CPS and the broader prosecutorial community.

To kick things off, I’m proud to co-author this first article with my longtime friend and fellow prosecutor, Robyn Beckham. Robyn serves as the Criminal Trial Chief in the Kaufman County Criminal District Attorney’s Office, where she often handles criminal cases that run parallel to CPS proceedings. Together, our goal is to offer practical guidance on building stronger, more effective lines of communication between criminal prosecutors and CPS attorneys. Drawing from our combined experiences, we hope to shed light on the mutual benefits of collaboration—and why reaching out to your CPS counterpart doesn’t just make the work easier but often leads to better outcomes for the cases and children we all care about.

Introduction from Robyn Beckham

Leslie is right: A CPS caseload can seem to the rest of us like it operates on its own island, complete with its own “island time” (thanks to unfamiliar ticking statutory clocks) and “island language.” If you’ve ever attempted to review a CPS narrative and seen something like, “FP is UTD for PHAB to OV; however, TMC granted due to NSUP of OV and SB, and CASA is appointed,” you know exactly what I mean. It can feel like you need a translator to figure out what’s going on.

But once Leslie walked me through the wealth of knowledge and resources available to CPS attorneys, I realized how valuable that information could be to my own work as a criminal prosecutor. Simply put: The earlier we share information and collaborate, the stronger both our investigations and prosecutions can be. So let’s get this conversation started.

Leslie, what exactly is it that you do on your island? What is the role of a CPS prosecutor, and where do your legal authorities come from?

Leslie’s perspective on CPS: What I do and why

I will note at the outset that “CPS” is the common, all-encompassing way of referring to two separate programs within the Texas Department of Family and Protective Services: Child Protective Investigations (CPI) and Child Protective Services (CPS). These are two of four distinct programs within the Texas Department of Family and Protective Services serving our state and communities in its efforts to ensure the safety of children, adults, and families.[1]

CPS becomes involved when DFPS (sometimes just called “the Department”) receives an intake report containing allegations of the abuse or neglect of a child. But what exactly do those terms mean? Under Texas Family Code §261.001(1), (3), and (4), actions and inactions determined to be abuse, neglect, or exploitation include:

• physical, emotional, or sexual abuse;

• physical or medical neglect;

• sex or labor trafficking;

• neglectful supervision;

• abandonment;

• refusal to assume parental responsibility; or

• illegal or improper use of a child.

However, it’s important to note that CPS does not investigate reports where the alleged perpetrator does not reside in the child’s home or is not a legal guardian or family member of the child.

You might be surprised to learn that the role of a CPS prosecutor involves far more than just appearing in court for termination of parental rights cases. Let’s consider first that each report made to the Texas Abuse Hotline[2] creates a case with its own timeline. Some of those timelines are short, with CPS Statewide Intake closing the cases without requiring further investigation or involvement (for instance, reports involving allegations of abuse or neglect by a person “other than a person responsible for a child’s care, custody, or welfare”[3]). But other cases’ timelines can be much longer in length—perhaps even multiple years—if they follow the path of investigation, family-based safety services, and eventual legal intervention requiring CPS taking custody of the children.

When a case is determined to require further CPS investigation and involvement, it is referred to the appropriate local CPS office. That is how such matters occurring in Ellis County end up on my desk.[4] I provide legal counsel to CPI during the initial investigation of the case, as they determine whether children should be taken into custody, or, alternatively, whether services can be provided safely to the family while the children remain in the family home. I provide counsel when the case rises to the necessity of CPS taking legal custody and possession of children. I even continue to provide counsel to CPS if children remain in CPS care after the termination of parental rights.

How I can assist criminal prosecutors

Why does any of this matter to my criminal prosecutor counterparts? Because at each stage of a family’s involvement with CPS, we are gathering a wide range of information and evidence—about the children, their families, and the underlying issues that led to CPS involvement in the first place. Even if CPS doesn’t open a case that is ultimately referred for further investigation, the records of Statewide Intake will include the details of the initial report, as well as potential collateral information gathered during the screening process. In other words, even a closed CPS case may still contain valuable leads, especially if you’re building a criminal case against a parent or guardian.

This is why I encourage criminal prosecutors to reach out to your CPS attorney. We may be able to point you toward relevant records, explain case history, or help you access witnesses and information you didn’t even know existed. I am certain that criminal prosecutors have had cases they were working on in which they needed to locate a CPS investigator mentioned in the case report. Guess what? I can very likely provide you with the most up-to-date contact information for that person. Even more crucially, I can help you track down children who are no longer in their original guardians’ homes.

Envision the following scenario: You are prosecuting a mother charged with the physical abuse of her child. Your investigation reveals that CPS removed the child from his mother and terminated her parental rights. From your review of the records, you see that the child was adopted by a foster parent. Then the trail goes cold. Well, I can very likely obtain contact information for the foster parent. I may not always have the information you need, but we won’t know if we don’t try.

Now let’s hear from Robyn on how this has worked in practice. Robyn, what information have I helped you gather for some of your criminal prosecutions, and how did you use it?

Robyn’s criminal perspective: what I need from CPS

The CPS cases that most often overlap with criminal prosecution—and offer the richest potential for collaboration—are those involving the physical or sexual abuse of children. In these cases, working closely with a CPS attorney doesn’t just help; it can significantly strengthen the case at every stage, from investigation to trial.

Physical abuse. If you’re prosecuting a parent for Injury to a Child,[5] CPS’s concurrent investigation can be an invaluable source of information—and in some cases, it may provide even more compelling evidence than what your law enforcement team collected. Here’s what CPS may bring to the table:

• supplemental evidence collection: CPS caseworkers often take high-quality, close-range photographs of injuries, sometimes clearer and more detailed than those taken by police. Even more beneficial, these images are frequently taken in the child’s home, giving you additional documentation of the crime scene and the child’s living environment at the time of the offense.

• witness interviews: CPS caseworkers routinely speak with a broad range of people, including the child victim, siblings, caregivers, and even the alleged perpetrator. These interviews are sometimes audio- or video-recorded, and they often happen early in the process, before law enforcement is involved. That timing can result in spontaneous, unguarded statements. In fact, I’ve prosecuted cases where defendants made near-confessional statements to CPS caseworkers, only to change their stories when later questioned by police.

• reliable contact information: Even if CPS’s investigation doesn’t yield new evidence, caseworkers often have up-to-date contact information for the child’s protective guardians, which is critical for coordinating witness prep meetings or ensuring the child has a safe, supportive adult to accompany them to court.

But don’t stop at the open CPS file! Leslie knows that I always ask for all prior CPS investigations involving the same family, especially when prosecuting a charge of intentional injury to a child. Why? Because one of the most common defenses in these cases is that the defendant’s use of force constituted “reasonable discipline” under Texas Penal Code §9.61.[6] The best way to rebut this argument is by showing a history of prior physical abuse that clearly exceeds reasonable discipline, especially if it resulted in a history of visible injuries or multiple CPS interventions. Prior CPS records can provide additional context, helping to establish a history of excessive or escalating force that undermines the defendant’s claims.

Sexual abuse. These cases present unique challenges to criminal prosecutors: delayed outcries, limited or no physical evidence, and complicated family dynamics. Here, information gathered during a CPS investigation can be uniquely helpful.

A CPS caseworker is sometimes the first professional to hear the child’s account of abuse. Her documentation may capture the child’s first verbal disclosure of the abuse to an adult, including the child’s description of the act(s), a timeline of when events occurred, and the child’s behaviors or emotional responses during the interview. This early contact can be pivotal; in fact, the CPS caseworker may qualify as the outcry witness under Code of Criminal Procedure (CCP) Art. 38.072, making the child’s hearsay statement to her admissible in court.

In some cases, CPS records may reveal prior allegations of sexual abuse against the same offender, whether from the current victim, other children in the household, or unrelated minors. This evidence may support the admissibility of extraneous offenses or acts under CCP Art. 38.37, which the jury can hear in the guilt–innocence phase of trial and consider for all purposes, including the character of the defendant. CPS caseworkers sometimes elicit useful information from the defendant’s family members about prior grooming behaviors and other red flags they noticed but failed previously to report, and this can become powerful corroborating evidence for a jury at trial.

At a minimum, CPS risk assessments and home studies can help us understand the child’s living environment, family structure, and available support. This information allows prosecutors and victim assistance coordinators (VACs) to create a safety plan with the family, identify appropriate services, and make counseling referrals as needed.

CPS collaboration is also key in reducing secondary trauma for child victims. By coordinating early and ensuring that forensic interviews are scheduled appropriately, you can avoid unnecessary duplication, delays, or conflicting instructions. This coordinated effort ensures that the child receives trauma-informed care from the outset.

Child homicide or serious bodily injury (SBI) cases. When you’re handling a case involving the death or serious bodily injury of a child, CPS records become even more critical. These are the most tragic, high-stakes cases we prosecute, and CPS often has the most comprehensive timeline of the child’s final days. CPS caseworkers usually interview every available family member, sometimes several times, and may be the only professionals to establish congenial rapport with surviving relatives or caregivers. Their records of family contacts can help you:

• reconstruct the timeline leading up to the critical incident,

• identify inconsistencies in family members’ accounts, and sometimes even

• expose prior patterns of harm or neglect that build your case theory.

CPS attorneys have access to unique and powerful information, but you won’t benefit from it if you don’t ask. So, let’s ask!

Leslie, how do criminal prosecutors make a proper request for this critical evidence and information?

Leslie’s advice for gathering and interpreting CPS records

CPS uses a system called IMPACT (Information Management Protecting Adults and Children in Texas) to record the information gathered in cases. This will include the report to the Texas Abuse Hotline, notes and records from the initial investigation, and all evidence gathered through the subsequent stages of the case’s timeline. Only those employed by or contracted with CPS have access to this system. However, CPS has created a one-stop-shop website, which provides instructions on how to request the release of this information for use in the prosecution of a criminal case.[7]

I recommend that you request a copy of the entire case file from CPS, via a subpoena deuces tecum and/or court order.[8] Such a request should result in production of the entire case file, which may include any or all of the following: caseworker narratives, photographs, videos, audio recordings, court reports and/or orders, and treatment providers’ records.

I will warn you that certain types of evidence may be available only for a limited time. For instance, while internal CPS policy may provide for a longer preservation period, the Texas Family Code requires only one year’s preservation of the original recordings of the hotline reports.[9] For these reasons, I encourage you to make these requests as soon as possible, ideally in the pre-indictment, intake stage of a criminal prosecution.

Interpreting CPS records

Once you’ve received a copy of the case file, how do you read it? Robyn is right: It can look like a confusing alphabet soup. Let’s revisit the example she provided earlier:

“FP is UTD for PHAB to OV; however, TMC granted due to RTB / NSUP of OV and SB, and CASA is appointed.”

This particular set of acronyms is actually intended to communicate the following:

“The investigation into Foster Parent(s) has concluded with a disposition of Unable to Determine for Physical Abuse to the Oldest Victim; however, Temporary Managing Conservatorship has been granted due to Reason to Believe / Neglectful Supervision of the Oldest Victim and Sibling, and a Court Appointed Special Advocate has been appointed for the children.”

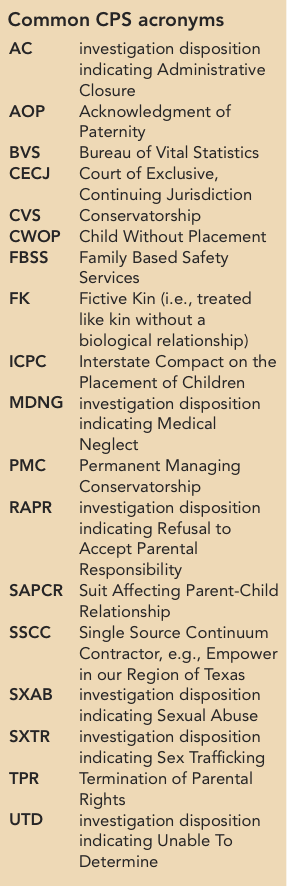

Clear as mud, right? For your convenience, I have listed some of the most common acronyms and abbreviations in CPS records in the sidebar below. If you would like additional resources to help you review CPS records, I will point you to the Texas Supreme Court Children’s Commission. It has created several helpful (and free!) bench books and attorney toolkits, including a more extensive glossary of CPS acronyms and abbreviations.[10]

Robyn, once you have received the CPS file, what are the criminal prosecutor’s next steps—both practically and ethically speaking—in handling that evidence?

Robyn’s considerations for criminal prosecutors with CPS evidence

When handling CPS records, don’t assume you have the full picture just because you received a set of responsive documents from your subpoena. CPS casefiles are often complex and cumulative. That means there may be addenda, supplemental reports, or updated narratives that were created after the initial production. That’s why I recommend treating CPS records the same way we treat law enforcement casefiles: with follow-up and verification.

I recommend a “trust, but verify” approach. In the same way I go item-by-item through the police agency’s evidence with the lead detective prior to trial, I schedule a similar pretrial meeting with the lead CPS caseworker assigned to the case. Here’s what that looks like in practice:

• Schedule a meeting well before trial with the lead CPS caseworker or Special Investigator. Use this time to go over the contents of the case file, clarify any confusing notations, and most importantly, ask if anything is missing or has been newly generated.

• Be specific in any follow-up subpoenas. If the caseworker references any additional interviews, assessments, or provider notes that weren’t in your original production, draft a narrowly tailored subpoena or court order for those specific items.

• Disclose early and often. As soon as you receive CPS records, promptly review them and disclose them to the defense. Delays in turning over these records can create major ethical and procedural pitfalls down the line.

• Add CPS personnel to your witness and expert lists. CPS caseworkers can be invaluable at trial, not only as fact witnesses, but also sometimes as expert witnesses on topics such as child development, grooming, and patterns of abuse.

Following these steps helps protect the prosecution’s timeline from unnecessary delays and ensures the case file is as complete and trial-ready as possible.

Ethical considerations

Is CPS “the State” for Brady or Michael Morton purposes? Short answer: No. CPS’s role is to ensure the safety and welfare of children, not to investigate or prosecute crimes. CPS may be looking into claims of abuse or neglect, but “that alone does not automatically transform CPS caseworkers into law-enforcement officers or state agents.”[11] This means that we, as criminal prosecutors, are not under an obligation to proactively seek out any and all CPS records that might conceivably exist in connection to a criminal defendant or child victim. However, if we do obtain CPS records or associated evidence, whether through subpoena or informal request, we must disclose them to the defense in a timely manner.

To stay ahead of potential issues, I have made it my practice to act in advance, requesting any CPS files that may be relevant to my criminal case in the intake stage of prosecution. This helps prevent last-minute surprises and gives me a chance to identify and turn over Brady material before the defense requests it or the court orders it.

Additionally, familiarize yourself with how CPS interviews of defendants can potentially trigger Miranda issues. Although CPS investigators are not police officers, certain actions, such as coordinating interviews with law enforcement or questioning a suspect in custody, can arguably render them “state agents” under Texas caselaw. See, for example, Cates v. State,[12] Harm v. State,[13] and Wilkerson v. State,[14] which explore when statements to CPS caseworkers might be suppressed if obtained without proper warnings.

And finally, what should you do if the criminal defense attorney asks you for CPS records you don’t already have in your possession? While we are not under an obligation (unless ordered by the court) to gather such records for the defense, I recommend that we issue our own subpoena to obtain the evidence. After all, we want a copy of anything the defense is getting so we have access to the same evidence they do. This will prevent you from being caught off guard by information the defendant may seek to introduce at trial. The defense may have equal subpoena power, but we have the responsibility to be ready. It’s better to know what’s out there than to be surprised by it in court.

Concluding thoughts

From Leslie: I hope this article has given my criminal prosecutor friends the nudge and inspiration they need to reach out to their local CPS attorneys. We have access to such a wealth of information—but we won’t know what criminal prosecutors need unless they ask! CPS spends so much time with the children and families on our caseload; you will find them to be very motivated to assist in creating positive outcomes for your criminal cases given the opportunity. Let’s build more bridges between our islands, one phone call and one email at a time.

To my fellow CPS attorneys, don’t be afraid to step off your own island occasionally. Seek out feedback from the criminal prosecutors regarding how CPS might be of further assistance in prosecuting their cases. Look for opportunities to improve the coordination of our efforts. And likewise, when you learn of positive outcomes in criminal prosecutions involving children or families on your CPS caseloads, share that information back to relevant CPS investigators and caseworkers. All of us benefit from receipt of positive news! While the criminal courtroom may seem foreign at times, strong partnerships lead to better outcomes—not just for us as professionals, but for the children and families we’re all working to protect.

From Robyn: I hope this article helps my fellow criminal prosecutors feel more equipped and confident to work alongside CPS. Whether it’s uncovering corroborating evidence, strengthening your trial witness lineup, or just getting the full picture of a child’s home environment, CPS attorneys are some of our best resources for information. At the end of the day, our shared goal is justice and safety for vulnerable children, and that means making the most of every resource, every record, and every relationship. Let’s keep the conversation going.

[1] To learn more about the four major programs of the Texas Department of Family and Protective Services, visit www.dfps.texas.gov/about_dfps.

[2] 800/252-5400 or www.txabusehotline.org.

[3] Tex. Family Code §261.301.

[4] My point of view here is specifically from that of the solo CPS prosecutor in my office; other counties—those medium and larger-sized prosecutor offices—may have a team of CPS prosecutors, and still other counties rely entirely on regional CPS counsel employed by CPS.

[5] Tex. Penal Code §22.04.

[6] (a) The use of force, but not deadly force, against a child younger than 18 years is justified:

(1) if the actor is the child’s parent or step-parent or is acting in loco parentis to the child; and

(2) when and to the degree the actor reasonably believes the force is necessary to discipline the child or to safeguard or promote his welfare.

(b) For purposes of this section, “in loco parentis” includes grandparent and guardian; any person acting by, through, or under the direction of a court with jurisdiction over the child; and anyone who has express or implied consent of the parent or parents” (Tex. Penal Code §9.61).

[7] dfps.texas.gov/policies/Case_Records/ professional_duties.asp.

[8] Email your request with a subpoena deuces tecum and/or court order for release of records to records@dfps.texas.gov.

[9] Tex. Family Code §261.310(d)(3).

[10] benchbook.texaschildrenscommission.gov/index.

[11] Harm v. State, 183 S.W.3d 403, 407-08 (Tex. Crim. App. 2006); see also Cates v. State, 776 S.W.2d 170 (Tex. Crim. App. 1989).

[12] Cates v. State, 776 S.W.2d 170 (Tex. Crim. App. 1989).

[13] Harm v. State, 183 S.W.3d 403 (Tex. Crim. App. 2006).

[14] Wilkerson v. State, 173 S.W.3d 521 (Tex. Crim. App. 2005).