By W. Clay Abbott

TDCAA DWI Resource Prosecutor in Austin

In October 2004, I started in this position at TDCAA.

For the first several years, much of my time was spent crisscrossing the state of Texas pleading with prosecutors and police to get search warrants for blood in DWI cases. And we did. Things got even more lively in 2013 when the Supreme Court of the United States returned Missouri v. McNeely.[1] Suddenly it was easy to convince police to get blood search warrants. Every jurisdiction in Texas started doing just that.

There is always a downside and unintended consequences to any great change. Only in 2014 did I start to wonder just what a massive influx of blood kits would do to our labs. And the answer is: We buried them alive. (I am lucky anyone at the DPS Lab still speaks to me.) More blood kits require more testing, and DPS has also expanded the number of substances it tests for in toxicology. These blood cases also go to court.

All of which has led to this request, below, from Trevis Beckworth at the DPS Lab in Austin. It is probably way overdue. Please give it a careful read.

From Trevis Beckworth

Assistant Lab Director

Department of Public Safety in AustinIn addition to analyzing thousands of blood toxicology cases annually, the Texas DPS Crime Laboratory also serves as the permanent storage facility for all toxicology kits collected by the Texas Highway Patrol. These kits present a unique challenge because they must be refrigerated until their final disposition. Over time, the crime lab has accumulated more than 50,000 kits due to a lack of authorization for disposal. This high volume nearly maxes out the lab’s storage capacity, making it crucial for Texas prosecutors to help expedite the authorization process for their destruction.

Following the implementation of Article 38.50 in the Code of Criminal Procedure in 2015, the lab adopted a disposition process that mandated a judge’s signature, ensuring compliance with all notice and retention requirements. This prevented officers and prosecutors from authorizing the destruction of toxicology kits.

In September 2021, SB 335 came into effect, modifying and clarifying these provisions. Consequently, the crime lab transitioned to a process allowing prosecutors to grant destruction authorization. However, any case with an offense date before September 1, 2021, still requires a judge’s signature for authorization. This requirement has resulted in a significant number of cases in inventory that necessitate judicial attention and likely already exceed the immediate destruction eligibility date.

District and county attorney’s offices can play a role in addressing the current critical storage situation and preventing its recurrence. For older kits, the crime lab can provide your office with a list of aged cases in storage, which can then be routed to the appropriate court for disposition. These cases can be authorized for destruction either by using a Toxicology Disposition Form, or in bulk through a court order. For current cases, it’s highly advisable to consider waiving evidence preservation, as destruction can be authorized immediately upon case adjudication.

If you need information on cases in storage in your region or assistance with disposition documentation, please reach out to your nearest regional crime laboratory; find contact information for each one at www.dps.texas.gov/section/ crime-laboratory/contact-information.

Answering the call

In response to Mr. Beckworth’s request, remember that labs and prosecutors must exercise great care so we don’t destroy important evidence. Yet we clearly need to help. Reach out to your local lab and help them make space—without accidentally damaging the lab’s (and prosecutors’) credibility by destroying a needed blood kit.

In addition to blood kits that are tested for alcohol, the DPS Toxicology Lab tests blood kits for drugs and tests in those cases where there was a fatality. Like the alcohol testing lab, the DPS Toxicology Lab is seeking to shrink the size of the backlog by removing kits that no longer need testing. If you have cases that are not going to be prosecuted for whatever reason (no-file, the defendant went to the pen on other charges, or other reasons), please reach out to the DPS Toxicology Lab to remove them from the queue. Otherwise, those blood kits are still in line and delaying every other case where a prosecutor is waiting on a lab report for a plea or trial.

DPS has made great inroads in the last couple years in blood alcohol testing. There was some pain (moving kits around to address backlog) and some new contacts and procedures, but the process got better and faster. The legislature just sent the first big surge in funding to toxicology since we started burying them in blood kits in 2004. But that means change and a bit of discomfort.

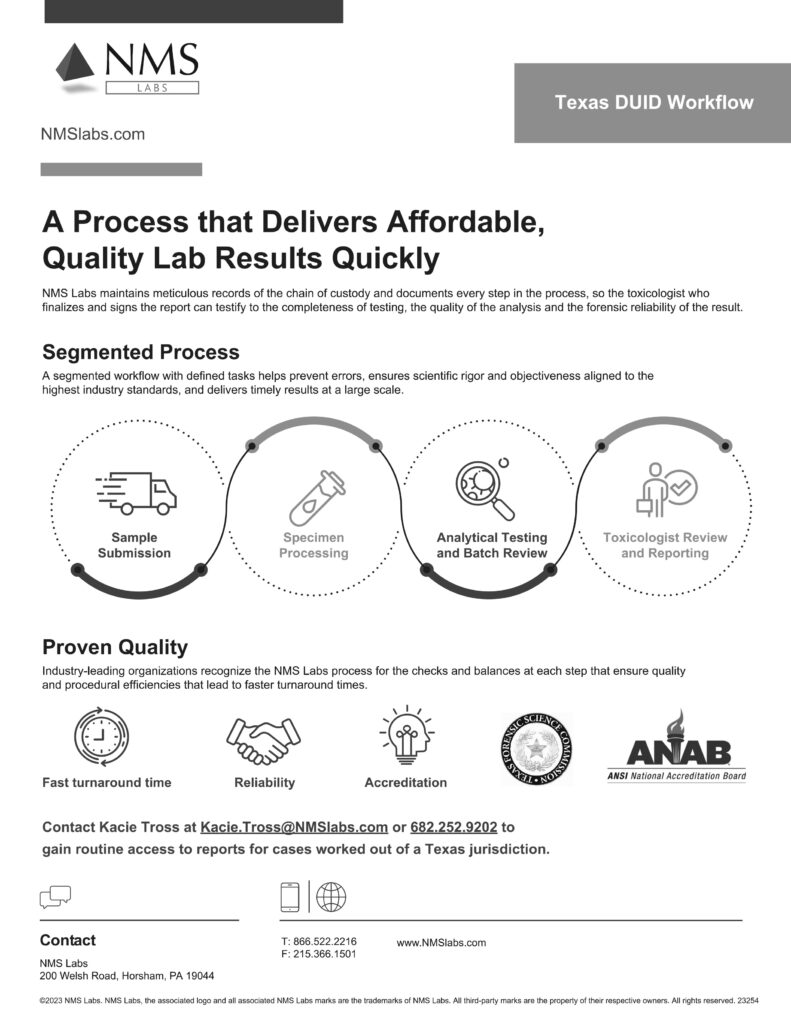

For instance, Toxicology will be outsourcing some of the backlog to NMS Labs. This will not be permanent, and effort is being made for DPS to keep cases involving injury and death. But some equalization is necessary to help the new funding, personnel, and equipment really work their magic.

Below is some info reprinted from NMS about the upcoming outsourcing. Watch our website at tdcaa.com/resources/dwi for additional information about labs.

Better communication gets everyone faster results. Better communication with the lab also means when your county’s name comes up at the Toxicology Lab because of a special request, there are good feelings and not frustrated ones. We constantly preach kindness and understanding for offenders and victims—how about some for our friends in the labs?

And please remember: The only folks in criminal justice who have a backlog greater than our misdemeanor divisions are those at the DPS laboratory. That fact alone should make us understanding allies.

Endnote

[1] 133 S. Ct. 1552, 185 L. Ed 2d 696 (2013).