By Monica Mendoza

TDCAA Research Attorney in Austin

The time has come for an update on the laws governing expenditures of hot check and asset forfeiture funds. The last update was in 2013,[1] and while the hot check provisions have essentially remained the same, several things with discretionary funds have changed. Below is a brief review of the rules governing hot check funds and a highlight of some of the most important asset forfeiture fund changes.

Hot checks

There are no significant changes to report regarding hot check fund administration. Code of Criminal Procedure Art. 102.007 provides that a county attorney, district attorney, or criminal district attorney whose office collects and processes hot checks and sight orders may collect a reimbursement fee from any person who is a party to the offense not exceeding:

• $10 if the face amount of the check or sight order does not exceed $10;

• $15 if the face amount of the check or sight order is greater than $10 but does not exceed $100;

• $30 if the face amount of the check or sight order is greater than $100 but does not exceed $300;

• $50 if the face amount of the check or sight order is greater than $300 but does not exceed $500; and

• $75 if the face amount of the check or sight order is greater than $500.[2]

The reimbursement fees must be deposited in the country treasury in a special fund to be administered by the attorney for the State. Expenditures from this fund are at the sole discretion of that attorney and may be used only to defray the salaries and expenses of the prosecutor’s office, but in no event may the attorney supplement his or her own salary from this fund.[3]

In addition to collecting a reimbursement fee, the attorney may collect a processing fee (a maximum of $30)[4] for the benefit of the check holder. However, keep in mind that while a processing fee may be collected, the attorney for the State may not charge a processing fee to a drawer or indorser if a reimbursement fee has been collected under Code of Criminal Procedure Art. 102.007(e). If a processing fee has been collected and the holder later receives a reimbursement fee collected under Art. §102.007(e), the holder must immediately refund the fee previously collected from the drawer or indorser.[5]

The rules governing expenditures of hot checks have not changed since our last update. The elected prosecutor still retains sole administrative discretion over the hot check fund and need not get commissioners court approval before making expenditures.[6] However, that is not to say the fund is free from all county oversight. The fund is still subject to audits by the county auditor,[7] and all interest that accrues on the account must be severed from the principal for the benefit of the county.[8] Any overages in a hot check fund go first to the defendant who paid it; then it escheats to the State if the defendant can’t be found.[9]

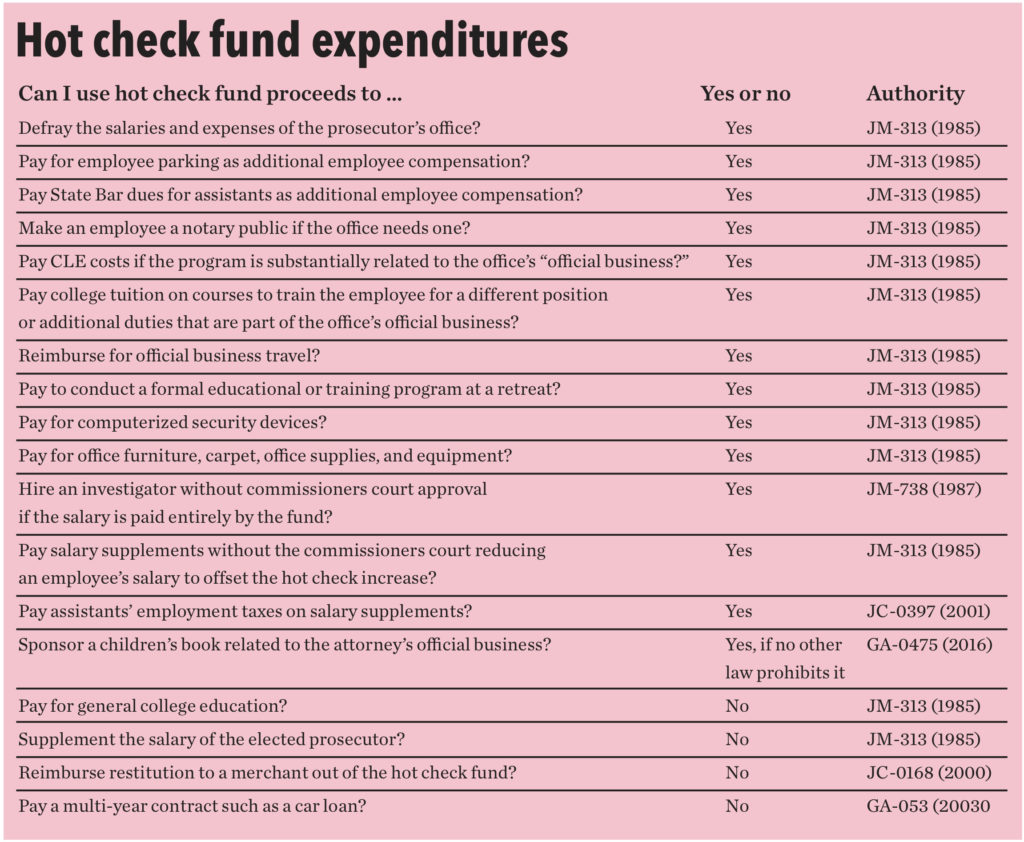

Most hot check expenditures guidelines come from Attorney General opinions, but prosecutors still proceed at their own risk when abiding by those opinions. They are purely advisory, and while they may be helpful, they have no legal force or effect. For a quick review on determining how to spend hot check funds, see the chart below.

Asset forfeiture funds

The legislature made several changes in 2013 to provide additional guidance on how proceeds or property received under Code of Criminal Procedure’s Chapter 59 can be used. The main purpose behind these additional subsections was to eliminate the need for frequent requests for Attorney General opinions about expenditures.

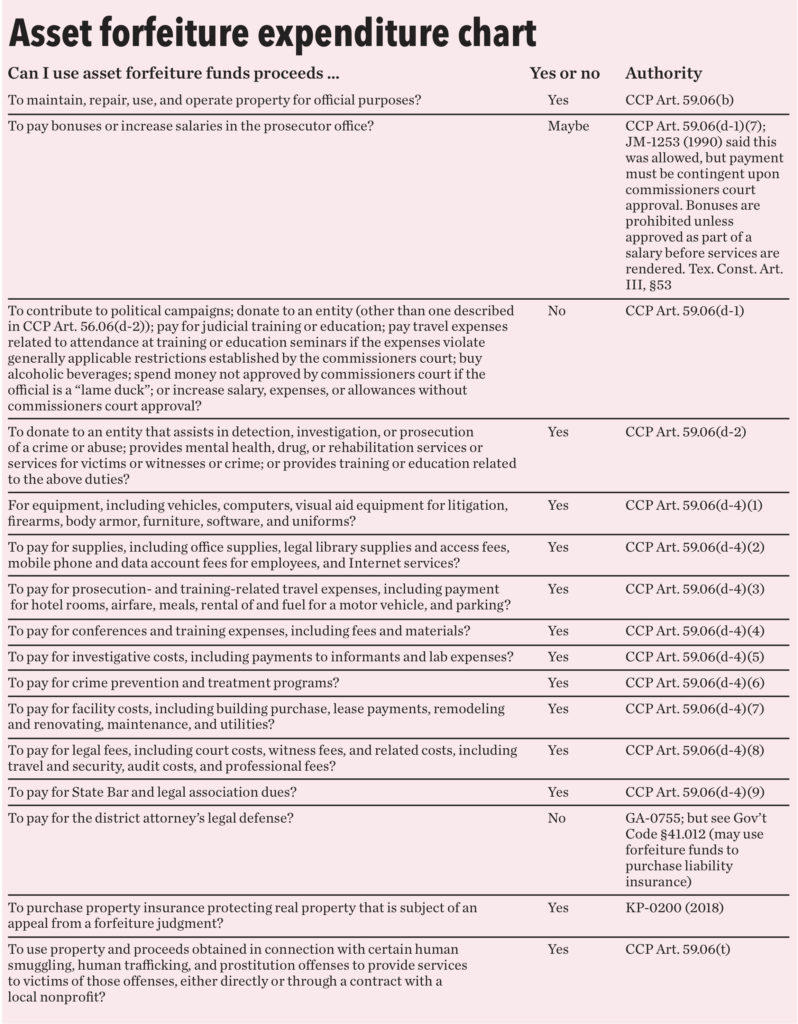

One of those major changes was adding Art. 59.06(d-4), which governs expenditures for prosecutors. Under Art. 59.06(d-4), attorneys representing the State may use proceeds or property “for an official purpose of an attorney’s office.” Comparably, the legislature also added Art. 59.06(d-3), which governs how law enforcement agencies may use proceeds received under Chapter 59. Under Art. 59.06(d-3), any expenditure is considered to be for “law enforcement purposes” if it is made for an activity of a law enforcement agency relating to the criminal and civil enforcement of state law. While these two provisions may look similar, they are not identical. For the purpose of this article and the chart on page 25, we will focus of some of the most important asset forfeiture fund uses related to prosecutors only.

Under Art. 59.06(d-4), an expenditure for “an official purpose of” a prosecuting attorney’s office is for an activity that relates to the preservation, enforcement, or administration of state laws, including equipment, supplies, prosecution- and training-related travel expenses, conferences and training expenses, investigative costs, crime prevention and treatment programs, facility costs, legal fees, and State Bar and legal association dues.

Despite the long list of examples in this new subsection, they are still only general lists. Nothing in (d-4) prohibits expenditures not listed in those subsections; the subsections merely say that the listed items within are a permissible expenditure. As long as an elected prosecutor’s expenditure of forfeited funds “relates to the preservation, enforcement, or administration” of a state law, “the fact that a particular expenditure is omitted from the examples listed in Art. 59.06(d-4) is not dispositive.”[10]

Perhaps the only true substantive change can be found in subsection (d-4)(7), which explicitly authorizes expenditures for “facility costs, including building purchases.” This would seem to overrule the conclusion of Attorney General Opinion GA-0613 (2008), which said that a district attorney could not use asset forfeiture funds to help purchase a juvenile detention facility for a county. With the inclusion of “building purchases” in (d-4)(7), an expenditure like that may now be acceptable because such a facility is related to administration of the Juvenile Justice Act.

Finally, in 2019, the legislature added Article 59.06(t), which requires property and proceeds obtained in connection with certain human smuggling, human trafficking, and prostitution offenses to be used to provide services to victims of those offenses, either directly or through a contract with a local nonprofit. For more specific examples of permissible and impermissible uses of these funds, see the full chart below.

Conclusion

With the addition of the changes in 2013 and no significant changes to the hot check fund administration, determining how to spend hot check or asset forfeiture funds should be a bit easier. Remember that you can always call the association at 512/474-2436 with questions you may have. We are here to help!

Endnotes

[1] Former TDCAA Research Attorney Markus Kypreos wrote the original article on asset forfeiture and hot check funds in 2005; Sean Johnson and Lauren Owens brought you updates in 2008 and 2013, respectively.

[2] Tex. Code Crim. Proc. Art. 102.007(c).

[3] Tex. Code Crim. Proc. Art. 102.007(f).

[4] Tex. Bus. & Com. Code §3.506.

[5] Tex. Bus. & Com. Code §3.506(c).

[6] Op. Tex. Att’y Gen. JM-0313 (1985).

[7] Op. Tex. Att’y Gen. GA-0053 (2003); Tex. Loc. Gov’t Code §115.032.

[8] Op. Tex. Att’y Gen. JC-0062 (1999); Tex. Loc. Gov’t Code §113.021(c).

[9] Tex. Loc. Gov’t Code §114.002.

[10] Op. Tex. Att’y Gen. KP-0200 (2018).