Art Clayton

Lisa Callaghan

Tarrant County prosecutors re-enacted a vicious murder in court, all narrated by the defendant himself as he testified from the stand. Their demonstrative display unraveled the murderer’s story and led to his conviction and a life sentence for killing his girlfriend and unborn daughter.

It is a sad fact that, for some, there is an exceedingly fine line between love and hate. Often, the fulcrum on which the difference rests is the idea of power, of control. When one person asserts independence or control over a situation, it can result in a display of explosive violence as the other person attempts to prove who is really in charge.

That was the case with Tracy Renee Anderson, a young woman in our county who was murdered by her boyfriend. In March 2014 she was pregnant with her first child, a girl whom she had decided to name Ashton Makenna Rae. On the day she died, she was 37 weeks pregnant, but both she and her baby were killed at the hands of the baby’s father, Robert Charles Atlas.

A tumultuous history

Tracy Anderson and Robert Atlas met in May 2013 on a dating website, Plenty of Fish. The two became close very quickly, but their relationship was a tumultuous one. Atlas once pushed Tracy down some stairs in July 2013, breaking her collarbone. A few months later, Tracy called the police because Atlas had assaulted her. He was also carrying on an affair with another woman, which Tracy discovered after coming home to her apartment at an unexpected hour and catching the two of them together.

The final documented altercation between the two occurred on February 1, when Atlas called police claiming Tracy was assaulting him and had gone for a gun. However, the 911 recording of the incident depicted Tracy only asking for the power cord for her phone after Atlas had locked himself in the room to wait for the police. Despite the fact that he said he was in a “life and death” struggle with her, this claim was not supported by the 911 tape at all. But Atlas’s claims of Tracy’s violence were eerie foreshadowing to what would happen less than two months later.

Tracy’s death

On March 21, Tracy Anderson went out to celebrate the birthday of her friend Nakaiya Walters. Tracy returned home after 1 a.m., texted Nakaiya to say she’d gotten in safely, and left again to meet Atlas at another bar. Witnesses reported that the couple argued at the bar and that Tracy left, ostensibly going home. She sent Atlas strongly worded texts telling him he would not be sleeping in the apartment that night—but he showed up at the apartment around 2:40 that morning, forcing open the front door.

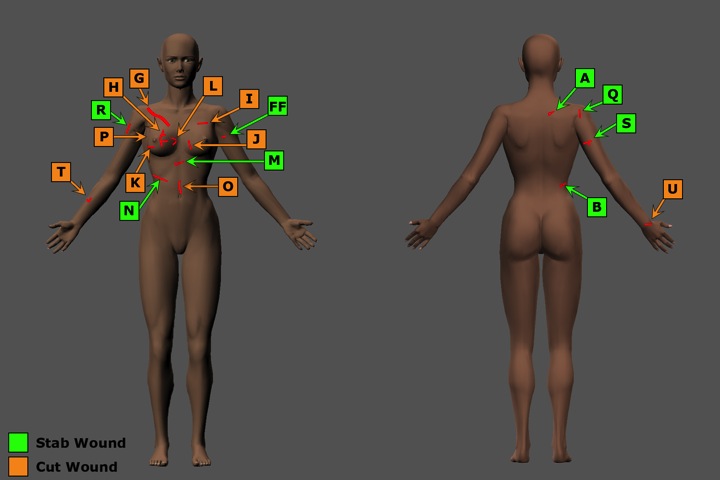

Only Atlas lived to tell what happened next, but physical evidence on the scene implied a violent attack. The bathroom door had been torn from its hinges and almost completely ripped in half, and it was lying on the living room floor when police arrived. (See the photo at the top of the opposite page.) It sported a partial footprint, which matched the shoes Atlas was wearing that night. (Again, check out the photo on the opposite page, middle.) The bathroom was a scene of horror: Blood coated the floor and closet door. Most of the blood was below doorknob-level, and a clear blood trail led from the bathroom into Tracy’s bedroom. (It was likely she had stumbled to the room for her phone, which was charging by the bed.) But she did not survive long enough to make a call; her naked body was found at the foot of the bed. Tracy had approximately 56 injuries all over her body, 36 of which were significant cut and stab wounds, with some as deep as 6 inches. Her unborn baby, too, had been stabbed, and she died as well.

After fleeing to Shreveport, Louisiana, Robert Atlas was arrested without incident, extradited to Texas, and charged with murder. From early on, he claimed self-defense in Tracy’s killing. In a recorded statement given to the police, the defendant claimed that the victim had attacked him with the knife, and that he inflicted all those wounds in self-defense.

He also initially claimed that he had inflicted only a few wounds, as though police would not be able to count them for themselves. He did not mention the wounds to the victim’s back, which could not have happened if he were truly defending himself from Tracy’s attack. He did not explain the truly horrifying number of defensive wounds to her hands and arms, and he also never explained why he left her dying and never tried to get her help—knowing that if she died, his child did too.

Demonstrations at trial

To counter Atlas’s story that he had stabbed Tracy and her unborn child out of self-protection, we prepared several visual aids for trial. Rhona Wedderien, the Digital Media Evidence and Trial Art Coordinator for the Criminal District Attorney’s Office, prepared Poser diagrams of Tracy and the baby (see the illustrations below) to show the exact locations of the wounds on their bodies. The wounds were numbered, just as they were in the autopsy, and we set up the presentation so that when we clicked the numbers in front of the jury, each was linked to the corresponding autopsy photo of the wound in question. It was an outstanding use of technology to make complicated expert testimony more accessible to jurors.

When we were laying out the trial photos and the diagram of the bathroom, Art had an epiphany: The room was too small for the offense to have occurred the way the defendant claimed it did. How could we show that to a jury? Art suggested a floor mat—like in the kids’ game Twister. After more conversation between the two of us, investigator Maria Hinojosa, and Rhona, the idea of a rubber mat was born. We envisioned a mat that was the exact dimensions of the bathroom where Tracy was killed and marked with the bathtub, sink, toilet, linen closet, and door. It was obvious to all of us that the defendant was likely to testify to tell his side of the story and even more likely to lie about what happened—the mat was a way to catch him in his lies, show the jury how the offense likely occurred, and back it up with objective evidence, such as the autopsy photos and blood spatter.

Trial work is all about effective communication. Our office is known for innovative trial presentations, such as mock video simulations, life-size cardboard cutouts of police officers (read an article on that particular trial in the Sept-ember–October 2012 issue of this journal or online here: www.tdcaa.com/journal/mother-all-%C2%AD demonstrative-evidence), and other creations that bring defendants’ crimes to life. This was an opportunity to use our skills once again to create an interesting, dramatic presentation that brought jurors to their feet and leaning out of the jury box to watch what was happening on the mat.

Rhona designed the mat with the assistance of the crime scene officers from the Bedford Police Department (they had taken measurements of the bathroom during their investigation), and she sent her design to a local contractor who works with our office. Because we did our own design, the cost was low, only $62.

The highlight of the trial was cross-examination. When I offered the mat as demonstrative evidence, both the judge and the defense attorney were a bit shocked—they had never seen anything like it before. The judge, however, quickly understood that it was really no different from any other demonstrative evidence. It was simply an aid to explain how the offense occurred—once we made clear that its dimensions were accurate. The defense objected, but they really had no basis except that they had never seen such a thing before. Defense objections were overruled, and we rolled out the mat.

Atlas is a good-looking man with a smooth speaking style, the kind who might have been difficult to cross-examine adequately. We asked the defendant to stand up so that he could clearly see the mat as it was laid out, and we asked him to position two volunteers who were the same height as the defendant and the victim (Chris McGregor and Maria Hinojosa, respectively, of our office) in the same position he and Tracy were in when the “self-defense” purportedly occurred. (See the photos, below.)

When he did so, it immediately became obvious the defendant was lying. First of all, he positioned himself and Tracy face to face on the bathroom floor, but the mat made it clear that the bathroom wasn’t big enough for them to be in that position. He also placed Tracy on her right side—but most of her stab and cut wounds occurred on her right side. He could not explain how that could happen if she were laying on her right side. He was also unable to explain how he stabbed her four times in the back in “self-defense.” When he left the witness stand, his credibility was in tatters.

Swift justice

The defendant was convicted in two hours and 20 minutes of capital murder and automatically sentenced to life without parole. This case was a marvelous example of teamwork in action. The Bedford Police Department worked as a team to put together a compelling case against the defendant, and Shreveport police worked with them to catch him after he fled to Louisiana. The prosecution team worked together to take the evidence from local police and paint a picture in the courtroom that no juror could mistake or forget. The result was that Mr. Atlas is now where he belongs: in the custody of the Texas Department of Criminal Justice. If hate is, as Euripides said in Medea, a bottomless cup, then it is one the defendant will have to drink alone in the Texas Department of Criminal Justice for the rest of his life.

Much of the practice of law is knowing and following precedent. Trial work, however, is where we can let our imaginations soar and try new and innovative things. We live in times when the expectations of jurors are often guided by television: They expect all the bells and whistles we can provide. Technology, when paired with out-of-the-box thinking, can provide fresh and compelling ways to present evidence. We would encourage other prosecutors to think about how we present evidence and experiment with new ways to bring a case to life.