By Staley Heatly

County Attorney in Wilbarger County

You’re in the middle of a family violence trial. You have called a couple of witnesses and laid the foundation for the case. The responding officer testified clearly, explaining how he arrived at the scene, observed the victim’s demeanor and injuries, and documented the incident. The scene photographs are good, showing redness on the victim’s cheek, a cut on her lip, and tears in her eyes. The pictures also demonstrate that the home was in disarray, with furniture toppled and a broken lamp on the floor. The 911 call has been played. The victim’s trembling voice can be heard asking for immediate police assistance. Everything is going well—at least, it has been. It’s time for the victim to testify.

As you sit next to her in the hallway just before she is set to take the stand, you sense that something has changed. She’s hesitant. She seems distant. Your stomach tightens. Then she tells you that she doesn’t remember what happened, that maybe she exaggerated, or she wants to “move on” and put the case behind her. It’s happening. She’s recanting. You can see the case slipping away and a repeat abuser walking free.

If you have prosecuted many family violence cases, you’ve likely been in this situation. You are about to call a witness to the stand, and you have no idea what she is going to say. One thing is sure, however: Whether the victim minimizes the incident or completely denies it, the defense attorney will rightfully pounce on this new version of events. During cross-examination, the defense will focus on every inconsistency and paint the victim as being unreliable at best and utterly dishonest at worst. The jury, unless adequately educated, will struggle to understand why an abused woman might minimize or even deny the abuse she allegedly suffered. If you don’t have a way to contextualize her behavior, the case will be in grave danger of falling apart. This is where an expert witness can save the day.

The role of experts

Expert witnesses provide juries with critical context about the dynamics of family violence. They can educate the jury on common victim behaviors that may seem like irrational or atypical responses to violence. These actions include recantation, minimization, delay in reporting, absence from trial, communicating with the defendant, and remaining in the relationship. A skilled expert will educate the jury that, rather than undermining the case, these behaviors are consistent with the dynamics of abuse and they support the conclusion that the victim is actually in an abusive relationship. Without that kind of expert testimony, jurors may fall back on common misconceptions, such as the belief that a victim would have left immediately if she were truly abused.

Circumstances at trial can change in the blink of an eye, and a cooperative victim may become reluctant or unwilling to testify due to fear, pressure from the abuser, or emotional turmoil. This is why it is crucial to always have an expert witness available or on standby in all family violence cases.

But I’m rural—I don’t have access to an expert witness

The most common complaint I hear from fellow rural prosecutors is that they don’t have access to family violence experts in their jurisdictions and don’t know where to find them. However, the real challenge isn’t necessarily a lack of qualified experts but rather the perception that local professionals don’t meet the requirements. While relatively few individuals formally market themselves as domestic violence experts, prosecutors can expand their pool of experts by identifying and qualifying professionals with extensive experience in the field, such as advocates, law enforcement officers, victim assistance coordinators, mental health professionals, researchers, and counselors who understand the dynamics of abuse. These individuals exist in every jurisdiction, and with a bit of training, they can serve as experts on the dynamics of domestic violence.

Who can be an expert?

Texas Rules of Evidence Rule 702 outlines the requirements for expert witnesses, stating that a witness may be qualified based on their knowledge, skill, experience, training, or education.[1] It is important to note that each of these qualifiers is separated by an “or” and not an “and,”—meaning an expert does not need an advanced degree, decades of experience, and extensive training to be qualified. Instead, expertise can be derived from specialized education, practical experience, the study of technical works, or a combination of these factors. Appellate courts have held that a detective with specialized family violence training, extensive case experience, and direct observation of victim behavior is qualified to testify as an expert on intimate partner dynamics.[2] Most law enforcement agencies in Texas will have at least one officer who meets these criteria.

A female assistant district attorney with extensive experience in family violence cases recently shared with me that she frequently uses male detectives or police officers with domestic violence experience as expert witnesses. She believes that having a male expert can help counter potential jury bias when both the prosecutor and victim are women. While law enforcement officers can be effective experts, especially those with specialized training in domestic violence, prosecutors should also consider whether a more independent expert might carry greater credibility with the jury. A police officer who was directly involved in the case, for example, may be perceived as biased or overly aligned with the prosecution. However, in situations where other expert options are unavailable, a well-qualified officer can serve as a valuable stand-in. In jurisdictions with multiple law enforcement agencies, prosecutors may consider using a qualified officer from a different agency who wasn’t directly involved in the case to provide a greater appearance of neutrality.

The key takeaway is that qualifying an expert in a domestic violence case is not an insurmountable challenge. It is well worth the time and effort to identify someone in your jurisdiction who, with a little training, can provide important contextual testimony when you need it. Appellate courts have affirmed the use of the following as experts on intimate partner dynamics:

• detective with training and experience;

• counselor in a police department;[3]

• social worker at women’s shelter;[4]

• counselor;[5]

• victim service coordinator at the police department;[6]

• forensic nurse/sexual assault nurse.[7]

The first family violence expert I ever used was a professor of counseling at nearby Midwestern State University. She had 20 years of experience as a counselor and had worked with many domestic violence victims. While she was an excellent witness, she had to come from an hour away to testify, so it wasn’t easy to have her on standby. In recent years, I have cultivated two expert witnesses in my small town, which has just over 10,000 people. One is a licensed professional counselor with experience counseling domestic violence victims, and the other is the executive director of our local family violence program, who has less than seven years of experience in the field. Both have come about their expertise in different ways, but they are both thoroughly qualified to testify. The counselor’s qualifications are evident: She holds an advanced degree, has specialized training in domestic violence, and possesses real-world experience working with survivors. The executive director, while not professionally trained, has spent years working directly with victims, engaging in safety planning, assisting with protective orders, handling crisis calls, and collaborating with law enforcement and prosecutors. Her practical experience makes her more than capable of explaining the realities of family violence to a jury. None of the experts I’ve used in family violence cases had PhDs or published articles on the subject at the time of their testimony. Those credentials aren’t required.

A few years ago, I had a victim who had entirely recanted her original statement in a letter to the defense attorney by the time we got to trial. She claimed that she had exaggerated everything and even lied about how her injuries occurred. While I made some helpful headway during her testimony, I could see that the jury was still confused. But then our expert testified about how victims minimize abuse and how abusers manipulate them into recanting. She explained how fear, financial control, and emotional abuse all play a role. During her testimony, I could see nods of understanding from members of the jury. It all came together. The case resulted in a conviction, and I firmly believe that the expert testimony made the case go from a close call to a 30-minute verdict.

If you are having trouble finding an expert witness, start by contacting the family violence program that serves your jurisdiction. The executive director or another experienced leader in the program may be your best option, as they often have years of direct experience in the field. Additionally, board members of these programs frequently hold professional degrees and possess expertise in domestic violence. Don’t overlook them as a potential source of experts. Even frontline advocates at family violence programs receive at least 40 hours of initial training, followed by ongoing annual education. Their training covers the dynamics of abuse, trauma response, barriers to leaving, and the impact of domestic violence on victims and children. More importantly, they spend their days working directly with survivors: helping them secure shelter, navigating the legal system, and rebuilding their lives. This firsthand experience provides a deep, practical understanding of family violence, which can be just as valuable as a formal degree when it comes to expert testimony.

If these sources don’t work for you, consider your office’s victim assistance coordinator or a victim advocate from another office or agency nearby. While the defense may make some hay related to their connection to your office, their testimony may be crucial in explaining the victim’s behavior in your case. The value of their testimony will far outweigh any argument the defense makes about their relationship with your office. After all, the witnesses are not there to advocate for the prosecution; they are simply explaining the dynamics of intimate partner violence and the expected behaviors of victims in these cases.

Preparing an expert

Once you have located someone with the necessary educational or practical experience, it’s time to start preparing her for court. You will want to go over the details of her testimony, the specific questions you plan to ask, and the types of questions she can expect on cross-examination.[8] Reviewing prior transcripts of expert testimony is particularly useful as it provides insight into how other experts have structured their responses and handled tough questioning during cross-examination. Because cross-examination is often the most nerve-wracking part for new experts, studying past exchanges can help them anticipate challenges and respond with confidence. The expert should also spend some time reviewing relevant resources to reinforce her general knowledge and understanding. There are numerous online websites and journals dedicated to intimate partner violence that are relevant to understanding victim behavior.[9] The Battered Women’s Justice Project offers an online guide designed to assist first-time expert witnesses in domestic violence cases.[10] While the witness needs to refresh her general knowledge, her testimony will not be based on what she has read in studies or research. Instead, it will come from her training and what she has learned by working directly with victims of abuse. The testimony is not an academic exercise but rather an explanation of how things work in the real world with real victims.

These fundamental preparations, combined with thorough trial preparation with the prosecutor, should ensure that the expert is well-prepared for trial. However, for those looking to take their readiness a step further, the Institute of Domestic Violence and Sexual Assault at the University of Texas offers free remote expert witness training.[11] While not a requirement for qualifying as an expert witness, this training comes highly recommended. It provides invaluable insight into the unique challenges of testifying, highlights common pitfalls to avoid, and offers best practices for effectively conveying expert opinions in domestic violence cases.

Now that you have located a person and provided her with some preparation and training, you are ready to go.

Qualifying the expert

As a standard practice, my office lists both of our family violence expert witnesses in the Notice of Expert Witnesses for all family violence cases. However, merely designating someone as an expert does not mean the defense will accept her qualification without challenge. At trial, always anticipate that the defense attorney will request to voir dire the witness on her qualifi- cations.

If the defendant requests a Rule 705(b) hearing under the Texas Rules of Evidence, the court must conduct it outside the jury’s presence. It is error to deny this hearing. During the hearing, clarify for the judge that the expert will not be offering an opinion on an ultimate issue of fact for the jury, such as if the defendant is a batterer or whether the victim was abused. Addressing these questions upfront can streamline the admissibility ruling. Be fully prepared to conduct the entire direct examination of the expert outside the jury’s presence, ensuring the judge has a complete understanding of her qualifications and the relevance of her testimony before ruling on admissibility. Before the hearing, thoroughly review the expert’s testimony and potential questions with her. Be open to her feedback and adjustments to strengthen the presentation. A well-prepared expert can make all the difference in overcoming admissibility challenges and ensuring the testimony is both persuasive and compelling.

Testifying

Once the judge qualifies the expert witness to testify, begin by having her introduce her occupation and qualifications to the jury before transitioning into a broader discussion of family violence dynamics. Highlight the specific strengths that make this witness particularly credible and knowledgeable. If the expert has extensive firsthand experience, such as counseling thousands of victims as an advocate, emphasize her real-world knowledge and direct victim interactions rather than focusing on academic credentials. If the expert is a law enforcement officer, underscore her practical experience by discussing the hundreds of domestic violence cases she has investigated, any special training she has received, and the number of victims she has worked with directly. Tailoring the emphasis to the expert’s strengths builds credibility with the jury. You don’t need to ask every possible qualifying question—just focus on those that highlight your expert’s particular strengths and experiences in a way that will resonate with the jury. For example, no one expects a police officer or victim advocate to have published articles on the dynamics of intimate partner violence, so there’s no need to ask that question if it doesn’t apply. Once the qualifications are established, shift the focus to a general discussion of family violence, setting the stage for how her expertise applies to the facts of the case.

At this point, you will want to ask questions such as:

• “How many family violence victims have you worked with?”

• “What are some common myths and misconceptions about family violence?”

• “Is there a local family violence shelter? If so, how much space is available at the shelter?”

• “Do family violence victims often recant?”

• “Do they frequently want the case dismissed? What are some of the reasons you have seen?”

• “Do some victims return to the relationship? Why?”

A detailed outline of sample questions for an expert witness can be viewed at the end of this article, below.

Explaining the dynamics of domestic violence

Once the basics have been covered, the next step is to provide the jury with a broader understanding of family violence dynamics. Texas courts have long recognized that testimony about the behavior patterns of victims and abusers is admissible, even when the expert has no personal knowledge of the individuals in the case. [12] The purpose of this testimony is not to offer an opinion on the specific facts of the trial but to educate jurors on the underlying pattern of domestic violence, helping them interpret the victim’s actions and the defendant’s behavior within a well-established framework.

Two of the most fundamental concepts in this area are the Cycle of Violence and the Power and Control Wheel. These models, supported by decades of research, have been widely accepted by Texas appellate courts as effective tools for explaining the realities of intimate partner violence.[13] To ensure clarity, use demonstrative exhibits to make the concepts more accessible to the jury. Ensure they are in a large format so that the jury doesn’t spend time squinting and trying to read fine print.

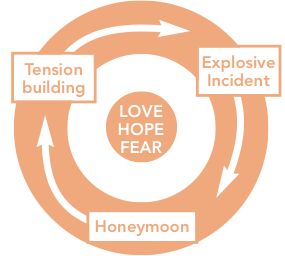

Cycle of Violence

Begin by having the expert explain the Cycle of Violence, also known as the Cycle of Abuse. This framework illustrates how domestic violence is rarely a one-time event but instead follows a repeating pattern that often escalates over time. Make sure to discuss the underpinnings of the cycle and how it is widely used today as a tool for explaining the dynamics of intimate partner violence.[14] The expert should discuss the following:

• Tension-Building Phase: The abuser becomes increasingly irritable, controlling, or aggressive, creating a climate of fear.

• Explosive Incident: The abuse occurs – whether physical, emotional, or psychological. It can range from angry yelling to physical or sexual abuse.

• Honeymoon Phase: The abuser apologizes, minimizes the abuse, and may temporarily exhibit loving or remorseful behavior to regain control. See the illustration, below, for a visual depiction of the Cycle of Violence.

Have the expert describe the devastating effect of the cycle on the victim and how victims react at each step. The expert should explain that the cycle repeats itself over and over, frequently resulting in escalating violence. Ensure that the expert discusses the nonviolent methods perpetrators can use to control their victim’s behavior, including verbal and non-verbal cues through body language. Once the violence has happened one time, a mere glance or a certain word can send a message to the victim that violence could happen again in an instant. This repeating cycle keeps the victim trapped in the abuser’s control.

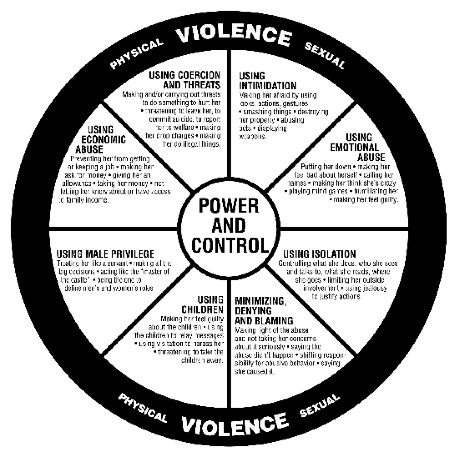

Power and Control Wheel

After explaining the Cycle of Violence, transition into a discussion of the Power and Control Wheel, which was developed in the 1980s by the Domestic Abuse Intervention Program in Duluth, Minnesota. (See an illustration of it below.) This tool categorizes non-physical tactics that abusers use to maintain control over their victims. The outer ring represents physical and sexual violence, while the inner ring outlines eight categories of coercive behavior commonly used by abusers.

The eight significant sections are broken down as follows:

• using intimidation,

• using emotional abuse,

• using isolation,

• minimizing, denying, and blaming,

• using children,

• using male privilege,

• using economic abuse, and

• using coercion and threats.

Each category has additional explanations included inside the wheel. For example, using male privilege includes “treating her like a servant, making all the big decisions, acting like the ‘master of the castle,’ and being the one to define men’s and women’s roles.” The expert should provide a brief explanation of each category, ensuring the jury understands how these tactics operate to entrap the victim.

But don’t stop there. While it is essential to educate the jury on the general aspects of family violence, prosecutors should take every opportunity to tie these specific concepts to the facts of the case. This can be done by highlighting testimony that is already in evidence and presenting it to the expert in the form of a hypothetical to demonstrate how the defendant’s behavior aligns with known patterns of abuse. For example, if testimony established that the defendant frequently left for the weekend without telling the victim, then came home late and demanded a meal upon his return, the prosecutor could ask: “If a victim described a partner who disappears for days without communication and then expects obedience upon his return, would that behavior align with the ‘male privilege’ category of the Power and Control Wheel?”

Similarly, if witnesses testified that the victim quit her job, stopped attending family gatherings, and became socially withdrawn after entering the relationship, the prosecutor could ask: “If a victim significantly reduces contact with family and friends after beginning a relationship, how does that align with the ‘isolation’ tactics used by abusers?”

Additional topics

Depending on the facts of the case, the expert should also address other critical issues that may arise in domestic violence trials, including:

• Victim minimization and self-blame: Many victims downplay the abuse due to psychological conditioning and trauma bonding. They blame themselves and not the abuser. This is typical victim behavior.

• Counterintuitive behavior: Jurors may wonder why the victim stayed in the relationship, returned after leaving, or refused to cooperate with the prosecution. The expert can explain the psychological, financial, or emotional barriers that commonly prevent victims from leaving their abusers.

• Domestic violence occurs in all demographics: Abusers come from all racial, economic, cultural, and religious backgrounds. A defendant’s status in the community, church, or workplace does not preclude him from being an abuser.

Important note

When utilizing an expert in a domestic violence case, it is crucial to align her testimony with her specific area of expertise. While a detective or police officer may be qualified as an expert on victim behavior based on her training and direct observations in past cases, her role differs from that of an advocate or researcher. Law enforcement experts should focus on real-world examples—how victims commonly recant, minimize abuse, delay reporting, continue dating the offender, etc.—rather than theoretical frameworks such as the Power and Control Wheel or the Cycle of Violence, which are better suited for advocates or academics. While this makes officers slightly less versatile as experts, their testimony remains credible and compelling. Many jurors may find firsthand experience with victims more relatable and persuasive than abstract theories.

Conclusion

Expert witnesses are invaluable in family violence cases, providing jurors with the context they need to understand victim behavior and the broader dynamics of intimate partner violence. By carefully selecting and preparing experts, you can ensure that their testimony effectively educates the jury and strengthens your cases. Whether law enforcement officers, advocates, counselors, or other qualified professionals, the right experts can make the difference between a conviction and an acquittal. Prosecutors, especially those in rural areas, should take the time to identify potential experts in their communities and work with them in advance of trial. With proper preparation, expert testimony can be a powerful tool to counter defense arguments, explain victim behavior, and ultimately hold abusers accountable.

[1] Tex. R. Evid. 702; Jensen v. State, 66 S.W.3d 528, 542 (Tex. App.—Houston [14th Dist.] 2002, pet. ref’d).

[2] Dixon v. State, 244 S.W.3d 472, 479 (Tex. App.—Houston [14th Dist.] 2007, pet ref’d) (court upheld expert testimony of detective who had received specialized training, worked at least 300 cases involving domestic violence, and observed trends related to victim behavior).

[3] Brewer v. State, 370 S.W.3d 471, 474 (Amarillo 2012, no pet.) (allowing a counselor in the family violence section of a police department to provide expert testimony regarding the three-stage cycle of violence).

[4] Coker v. State, Tex. App. 6450 (Tex. App.–Dallas July 29, 2019, no pet.) (mem. op., not designated for publication) (permitting a counselor and social worker at a women’s shelter to testify about the cycle of violence).

[5] Runels v. State, 2018 Tex. App. LEXIS 9995 (Tex. App.—Austin Dec. 6, 2018, pet. ref’d) (mem. op., not designated for publication) (a counselor’s testimony based on concepts of the cycle of violence and the power and control wheel was sufficiently reliable to allow the counselor to testify as an expert).

[6] Booker v. State, 2009 Tex. App. LEXIS 5541 (Tex. App.—Dallas Jul. 13, 2009, no pet.) (not designated for publication) (the victim services coordinator at a police department qualified as an expert witness in domestic violence).

[7] Davis v. State, 2020 Tex. App. LEXIS 6841 (Tex. App.—Dallas Aug. 25, 2020) (not designated for publication) (holding that a person who was both a forensic nurse and sexual assault nurse examiner was qualified to testify regarding domestic violence).

[8] Visit www.tdcaa.com/journal for a transcript of a cross-examination; look for this article, and the transcript is attached to it as a PDF.

[9] The National Domestic Violence Hotline has excellent general information at www.thehotline.org. For a general overview of domestic violence, Psychology Today has several articles at www.psychologytoday.com/ us/basics/domestic-violence.

[10] https://bwjp.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/DV-Expert-Witnesses-Tips-to-Help-You-Prepare-FINAL-CP-FIX-11-17-2017.pdf.

[11] https://sites.utexas.edu/idvsa/training-programs/expert-witness-training.

[12] Scugoza v. State, 949 S.W.2d 360, 363 (Tex. App.—San Antonio 1997, no pet.); Hill v. State, 392 S.W.3d 850, 855 (Tex. App.—Amarillo 2013, pet. ref’d) (finding expert testimony would aid the jury in understanding victim’s actions and resolving conflicts in her trial testimony); Harris v. State, 133 S.W.3d 760, 774 (Tex. App.—Texarkana 2004, pet. ref’d) (cycle of violence testimony relevant to explain victim’s behavior).

[13] Brewer v. State, 370 S.W.3d 471, 474 (Tex. App.—Amarillo 2012, no pet.) (finding testimony concerning “cycle of violence” assisted jury in understanding victim’s delay in calling police after assault); Foster v. State, No. 01-17-00537-CR, 2018 Tex. App. LEXIS 2855 at *14-15 (Tex. App.—Houston [1st Dist.] April 24, 2018) (mem. op., not desig. for pub.) (explanation of family violence dynamics, including the “power and control wheel” and the “cycle of violence” provided a helpful framework for understanding the victim’s behavior); Runels v. State, No. 03-18-00036-CR, 2018 Tex. App. LEXIS 9995 at *6 (Tex. App.—Austin Dec. 6, 2018, pet. ref’d) (mem. op., not desig. for pub.) (counselor’s testimony based on concepts of the “cycle of violence” and the “power and control wheel” sufficiently reliable to uphold determination that counselor should be allowed to testify as expert); Nwaiwu v. State, No. 02-17-00053-CR, 2018 Tex. App. LEXIS 6290 at *2-3 (Tex. App.—Fort Worth Aug. 9, 2018, pet. ref’d) (mem. op., not desig. for pub.) (determining that testimony from counselor, including portion explaining the “power and control wheel,” was reliable).

[14] The cycle was first described by Dr. Lenore Walker in her book The Battered Woman, released in 1979. In discovering this pattern, Walker interviewed more than 1,500 victims of domestic violence. The theory has been widely accepted in numerous works of social science including Bonnie S. Fisher; Steven P. Lab, Encyclopedia of Victimology and Crime Prevention, SAGE Publications; 2 February 2010, ISBN 978-1-4129-6047-2, p. 257.