By Brooke Grona-Robb

Assistant Attorney General, and

Cara Foos Pierce

Human Trafficking Section Chief, Office of the Attorney General, both in Austin

Human trafficking is occurring throughout Texas, every day, often in plain sight. Claims that “we don’t have a human trafficking problem here” are simply untrue. In fact, in the first 11 months of 2020, when so many industries were struggling because of COVID-19, the commercial sex trade flourished. According to research conducted by the Department of Public Safety, there were over 1.5 million online commercial sex ads in Texas in these 11 months, almost 300,000 of which contained suspected minors.[i] Not all commercial sex is trafficking, of course, but this is a clear indication that traffickers have flourished despite the pandemic. And while labor trafficking is more difficult to quantify, it is occurring in big cities and rural areas alike throughout Texas as well.

What trafficking is not

In order to effectively combat human trafficking, we must know what to look for. Human trafficking is not about children getting snatched from the local store and auctioned off to the highest bidder. Trafficking victims are seldom locked in cages or chained, and trafficking rarely starts with a guy in a white van grabbing a small child off a playground. Although the media often portrays trafficking akin to the movie Taken, that scenario is the exception, not the rule.

What trafficking is

Trafficking usually arises from a manipulative relationship that ensnares a teenager or young adult by fulfilling a basic need for food, shelter, or love. Traffickers find people in desperate situations, and they promise to make their victims’ lives better, so usually victims go with them willingly. Traffickers target runaways, foster kids, drug addicts, homeless people, undocumented immigrants, and those with mental illness or disability, for several reasons. First, these people are less likely to be missed if they disappear. Also, they are easy to manipulate because of their circumstances, so they will do as the trafficker tells them. Finally, they are less likely to be believed by law enforcement and the public if they manage to get away from the trafficker. While traffickers often use violence and threats of violence against victims and their family, the key to trafficking is coercion—emotional and psychological manipulation—to exert control over victims.

There is no “typical” trafficker. Traffickers are men and women, of all ages and ethnicities. Media portrayals of what a pimp looks like are merely stereotypes. While some traffickers drive fancy cars and wear expensive clothes, just as many blend in. They could be your neighbor who enslaves a domestic worker in her house, the owner of your favorite restaurant who holds his employee’s immigration papers, or the grandmother who owns the “spa” next to your local grocery store where two 16-year-old runaways are being trafficked for commercial sex.

As with traffickers, there isn’t a typical trafficking victim. They are both children and adults, both female and male. Their key common trait is vulnerability. They seldom outcry about the abuse and generally encounter the justice system first as offenders rather than as identified victims.

Trafficking law in Texas

Over almost 20 years, Texas has developed robust anti-trafficking criminal and civil statutes. Texas enacted its first human trafficking criminal statute in 2003. Since then, both the laws and the statewide anti-trafficking effort have increased considerably. Texas Penal Code Chapter 20A, which contains the human trafficking statute, has been amended almost every legislative session since its passage in 2003 to make it more expansive and giving it teeth.[ii] The changes have broadened the statute so that sex buyers and those who profit from trafficking enterprises are included. Additionally, punishment has increased in many situations, including the addition of a Continuous Trafficking statute, which creates a 25-year minimum sentence.

This statute punishes three crimes:

1) labor trafficking,

2) sex trafficking of a child, and

3) sex trafficking of an adult.

Notably, a “child” in this statute and others[iii] with a commercial exploitation aspect includes anyone under 18. For labor trafficking of children or adults, the statute requires the trafficker to have used force, fraud, or coercion to obtain labor or services.[iv]

To determine whether a set of facts constitutes human trafficking, first look to the definition of trafficking in §20A.01. To many people’s surprise, trafficking does not require a victim to be moved from one place to another. People sometimes confuse human trafficking, which is a crime against a person, with human smuggling, which is a crime against the U.S. border. While trafficking may include transporting a victim, it also includes enticing, recruiting, harboring, providing, or otherwise obtaining another person. For example, the fact that a person lives at a business where he works is a red flag that he may be harbored by a trafficker to obtain forced labor. Likewise, a recruiter for a sex- or labor-trafficking organization may be guilty of human trafficking even if he never had anything to do with transporting or harboring any victims.

Labor trafficking. Labor trafficking, found in §20A.02(a)(1), criminalizes trafficking another person with the intent that he engages in forced labor. Labor traffickers use some combination of force, fraud, and coercion to maintain control over victims. They often recruit with false promises of high wages or citizenship documents (fraud) and then use violence (force), threats of violence against the victim or his family (coercion), and confiscated identity documents (coercion) to keep victims from leaving. Labor trafficking occurs in the agriculture industry, as well as in restaurants, nail salons, and other storefront businesses we all visit.

People who benefit or profit from labor trafficking can be prosecuted under §20A.02(a)(2). The elements of labor trafficking are the same for child victims (§20A.02(a)(5) and (a)(6)), although child labor trafficking is a first-degree felony, while trafficking adults is a second degree.[v]

Sex trafficking of a child. What is commonly referred to as sex trafficking of a child or CSEC (commercial sexual exploitation of a child) is covered under §20A.02(a)(7). Sex trafficking of a child requires a showing that the defendant knowingly trafficked a child (under 18) and caused the child to engage in sexual conduct. Although the enumerated list of underlying conduct is long, it essentially covers all of the sexual crimes involving children. The State is not required to prove that the trafficker knew that the victim was under 18. Note also that all of the adults engaging in any part of this behavior are guilty of trafficking; those who profit as well as the sex buyer can be prosecuted under §20A.02(a)(8) for minor victims and §20A.02(a)(4) for adults.

Sex trafficking of an adult. Sex trafficking of an adult requires that a person knowingly traffics another using force, fraud, or coercion to cause the person to engage in prostitution activities. In a society that frequently punishes the sellers of sex more often and more severely than the buyers of sex, law enforcement and prosecutors sometimes raise the bar for what they consider force, fraud, or coercion higher than what legislators likely intended. Force is not defined in the Penal Code, so while it can certainly include handcuffs, chains, and bodily injury, force could also be obtained through a slap or by preventing someone from leaving the room by standing in front of the door.

While coercion includes various types of threats,[vi] in the context of adult sex trafficking it also includes withholding, destroying, or confiscating a person’s identification documents or government records, as well as forcing victims to use drugs or alcohol or withholding drugs from a person who is addicted to gain compliance.[vii] However, this expanded definition does not currently apply to labor trafficking absent the legislature passing a bill to create consistency in the definition of coercion.

Under the law, a person who previously engaged in prostitution activities willingly can still be trafficked. Pimps frequently target victims who are especially vulnerable, such as girls and women living at hotels and engaging in prostitution. Pimps want law enforcement and prosecutors to hold onto stereotypes about people engaged in prostitution activities so that they can continue to prey upon them. If someone does not want to work that night, at that location, or with that buyer, and a pimp uses force, fraud, or coercion to obtain acquiescence, that is trafficking. Trafficking can and should punish the people benefitting from the prostitution—the pimp and the customer, regardless of the history of the victim.

Trafficking punishments

Generally speaking, the punishment for trafficking is a second-degree felony when the victim is an adult and a first-degree felony when a child. However, a violation of §20A.03 (Continuous Trafficking) has a minimum of 25 years in prison regardless of the victim’s age. Continuous Trafficking occurs when any trafficking (sex or labor of adult or child) happens more than once over a period of 30 or more days. This isn’t simply limited to harboring a person for that time period. The crime could be committed by recruiting a person for forced labor that occurs once a month and transporting him to the worksite. Or it could mean that a child was recruited for prostitution on Day 1, and an adult was transported for forced prostitution on Day 31 by the same trafficker. The Texas statutes criminalizing trafficking and continuous trafficking are broad and carry serious consequences, and they are powerful tools for prosecutors—we should use them whenever appropriate.

Statute of limitations

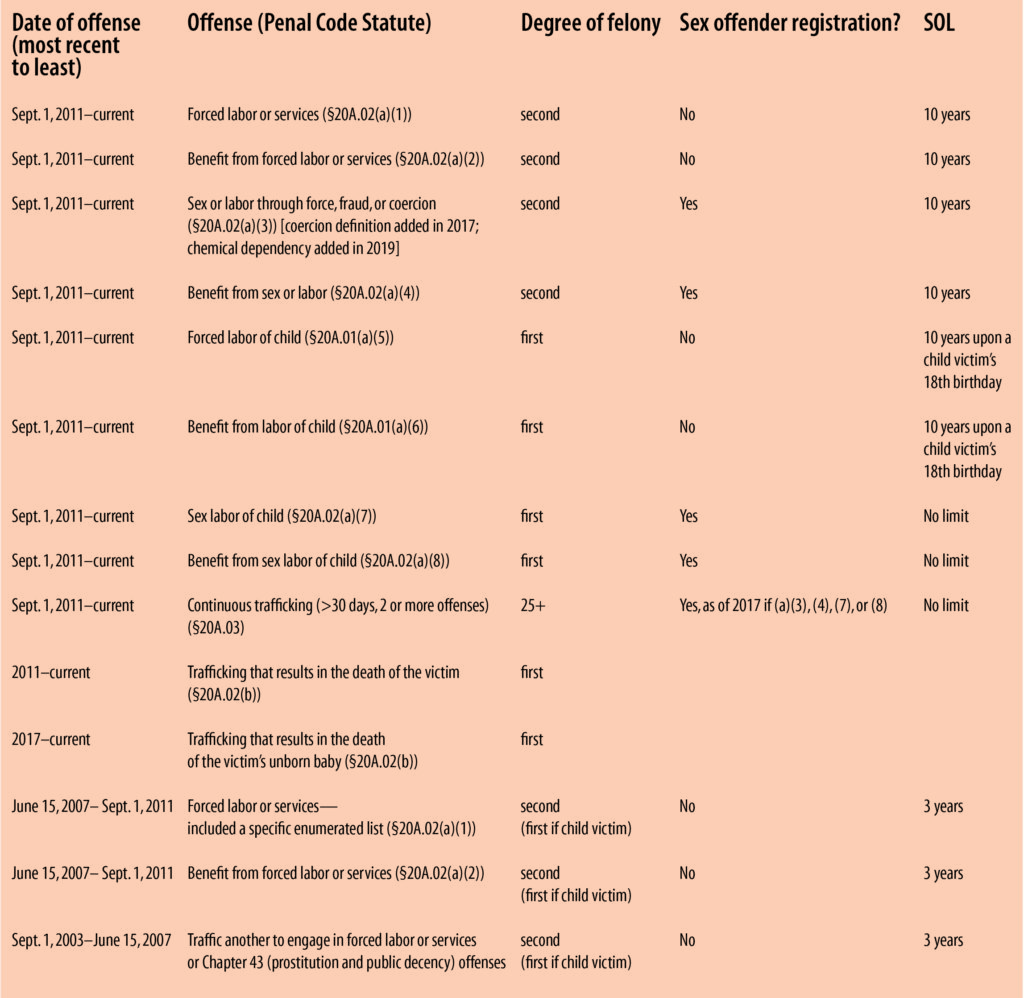

The statute of limitations in human trafficking has also been changed and extended over the last decade. In child sex trafficking cases, there is no statute of limitation, and there is a 10-year statute of limitations after the child’s 18th birthday for labor trafficking of children. The limitation for (sex and labor) trafficking of adults is 10 years from the offense date. Because the statute has changed a number of times over the last two decades, the chart below might help if you are looking to charge an offense that occurred several years ago. It also includes information about sex offender registration, which applies in child and adult sex trafficking cases.

Anti-trafficking resources

Research confirms what many of us have suspected all along: Victims fall into trafficking at an early age, and it takes a great deal of time and support to get out. A recent analysis of youth at risk for sex trafficking in Texas found that 33 percent of them were victimized during the last year. Once exploited, these youth spend 35 percent of their life in circumstances of exploitation.[viii] While not all victims are first trafficked as children, knowing that many are and that their cycle of exploitation continues unless disrupted is important.

As prosecutors, it is also important to note that trafficking victims often end up charged criminally themselves, sometimes as a direct result of their trafficking situation. Whether their trafficker made them hold drugs or he or she caused them to rob a sex buyer, you may find that a victim is also a defendant in your court. Be aware that they may not tell their lawyers or you that they are victims initially, or ever. The coercive nature of trafficking often delays victim outcries, so just because they did not claim they were forced to commit the crime from the beginning does not eliminate the possibility they were forced. This is a unique area of cooperation between prosecutors and defense lawyers. By learning the signs of trafficking, we can keep an eye out for potential trafficking victims in our courts. Trafficking is a defense to prostitution,[ix] and that defense should be considered by both the prosecutor and the defense handling a prostitution case. While committing a crime at the behest of a trafficker may not equate to a dismissal, it can be a mitigating factor in a plea offer or charge. And those defendants may benefit from services to prevent them from being victimized again and from reoffending.

Exciting things are being done statewide in response to trafficking, with many agencies across the state taking serious actions to address this problem. To help address trafficking, the Governor’s Office has given grants statewide to protect, recognize, and recover victims, support their healing, and bring justice to them and their traffickers. Such grants have supported protective programs such as Texas CASA and the Texas Alliance of Boys and Girls Clubs, among others.

Many communities across the state have created multi-disciplinary teams (MDTs) to gather and discuss how they are approaching the problem of trafficking. The Governor’s Office has supported adding advocates for child victims of sex trafficking, who develop long-term relationships with these survivors to assist with recovery. Grants have also supported care coordinators, who focus on the system’s response to the trafficked child by engaging in emergency staffing and MDTs.

Why are MDTs for trafficking victims needed? Can they just fit into the child abuse MDT? Although each community is different, it is important that any MDT truly addresses the unique nature of trafficking victims. Traditional child abuse MDTs are focused on the crime, making sure that everyone on the team communicates what they know so that the proper charge can be filed and the child’s needs can be addressed. In contrast, trafficking MDTs often need to focus on the victim’s current and future situation. Many trafficking victims fall through the cracks: They don’t outcry so they can’t get Crime Victims Compensation resources, they run immediately from placement, their homes are unstable, and follow-up care doesn’t occur. An HT MDT must bring all the people involved with that victim to the table to discuss what resources are working and which ones are failing and to decide how best to help the victim recover. Investigative and prosecution discussions in HT cases are important, but the first focus has to be stabilization of the child. This takes a great amount of time and endless energy poured into finding a solution that is as unique as each child. If given the opportunity to participate in an HT MDT, prosecutors can learn about their benefits.

Along with trafficking-specific MDTs, local anti-trafficking task forces and coalitions are key to serving victims in their communities. Below are the ones who have regular participation by prosecutors and law enforcement:

Area Task Force/Coalition

Bastrop County Bastrop County Coalition Against Human Trafficking

Bell County Central Texas DMST Roundtable

Bexar County Alamo Area Coalition Against Trafficking (AACAT)

Brazoria County Brazoria County United Front Coalition

Collin County Collin County Children’s Sex Trafficking Team (C3ST)

Dallas County North Texas Coalition Against Human Trafficking

Dallas & Tarrant Counties North Texas Anti-Trafficking Team (NTATT)

Denton County C7 (Denton County Human Trafficking Coalition)

El Paso County El Paso County Anti-Human Trafficking Task Force

El Paso County El Paso JPD Human Trafficking Task Force

Gregg County East Texas Anti-Trafficking Team Partners in Prevention

Harris County Houston Area Council on Human Trafficking (HAC-HT)

Harris County Houston Rescue & Restore Coalition

Harris County Human Trafficking Rescue Alliance (HTRA)

Hidalgo County Rio Grande Valley Human Trafficking Coalition

Jefferson County Southeast Texas Alliance Against Trafficking (STAAT)

Lubbock County Human Rescue Coalition

Lubbock County Sex Trafficking Allied Response Team (START)

McLennan County Heart of Texas Human Trafficking Coalition

Montgomery County Montgomery County Human Trafficking Coalition

Nueces County Texas Coastal Bend Border Region Human Trafficking Taskforce

Potter County Freedom in the 806 Coalition Against Trafficking

Smith County Network to End Sexual Exploitation (NESE)

Tarrant County Tarrant County 5-Stones Task Force

Taylor & Jones Counties Big Country Coalition Against Human Trafficking

Travis County Central Texas Coalition Against Human Trafficking (CTCAHT)

Travis County Central Texas Human Trafficking Task Force

Williamson County WilCo Human Trafficking Coalition

Along with these regional groups, Texas has a statewide task force to combat trafficking. The Texas Human Trafficking Prevention Task Force’s 2020 report came out in December, with a summary of initiatives and collaborations that reach across the state. And the Texas Human Trafficking Prevention Coordinating Council, which is made up of leader agencies in the task force, released its strategic plan in May 2020. That plan includes strategies to partner, prevent, protect, prosecute, and provide support for victims of human trafficking.

Prosecution assistance

As the regional coalitions help victims, the Human Trafficking and Transnational/Organized Crime Section (HTTOC) of the Texas Attorney General’s Office exists to help local prosecutors throughout the state with human trafficking cases. Human trafficking happens in every part of Texas, and cases can have unique challenges. They take considerable time and resources that not every local prosecutor has. The Texas AG’s HTTOC section wants to help.

HTTOC has six experienced prosecutors with more than 25 years of collective human-trafficking prosecution experience and more than 80 years of prosecutorial experience. HTTOC also partners with a team of AG Criminal Investigation Division Human Trafficking Investigators who work with local law enforcement across the state, and we have a victim advocate. We are available to help in four ways:

• provide in-person and online training for prosecutors and investigators on various human trafficking related topics,

• partner on human trafficking investigations and cases by being a second chair and assisting with prosecutions,

• lead prosecutions at an elected prosecutor’s invitation (when we have the time and resources to work on these cases), and

• advise prosecutors and law enforcement through our 24/7 duty line, the HT Blue Line, at 512/936-1938. Call with any human trafficking investigation or case questions.

We would love to talk with you about your cases, discuss whether our analytical or investigative resources can assist, or partner to make sure all prosecutors across the state recognize trafficking and are armed with all the tools they need to achieve justice for the victims of trafficking.

Endnotes

[i] DPS analysis of commercial sex internet sites, unpublished.

[ii] Amendments in 2007, 2009, 2011, 2015, 2017, and 2019.

[iii] Child pornography and sexual performance of a child, for example.

[iv] §§20A.01(2), 20A.02(a)(1).

[v] Trafficking of adults becomes a first degree if it results in the victim’s or the victim’s unborn child’s death. §20A.02(b).

[vi] §1.07(9).

[vii] §20A.02(a-1).

[viii] Kellison, B., Torres, M. I. M., Kammer-Kerwick, M., Hairston, D., Talley, M., & Busch-Armendariz, N. (2019). “To the public, nothing was wrong with me”: Life experiences of minors and youth in Texas at risk for commercial sexual exploitation. Austin, TX: Institute on Domestic Violence & Sexual Assault, The University of Texas at Austin.

[ix] Tex. Penal Code §43.02(d).